SCRIPT NOTES: Major Character Types – “Protagonist”

Characters are engines that drive ideas into story. Each of the five major character types plays a specific role in that process. First is THE PROTAGONIST.

WGA writer Michael Tabb has written for Universal Studios, Disney Feature Animation, comic book icon Stan Lee, and other industry players. Michael's new book, Prewriting Your Screenplay: a Step-by-Step Guide to Generating Stories, is available now. Follow Michael on Twitter @MichaelTabb and Instagram @michaeltabbwga.

Whenever agents, producers and executives are asked what they are looking for (regardless of genre or budgetary scope preferences), the answer always includes the phrase "character-driven." Everything else changes with trends and taste. Therefore, since the one constant everyone is always hungry for in Hollywood is great characters, it's obvious my first few articles on what I do should focus on how working screenwriters perceive, develop and quantify the characters that fill our scripts. Last month, my article WHO IS THE HERO serves as a prequel to this six-article series on the major character types (not to be confused with character archetypes). Along the way, some of the details will undoubtedly include information you already know, but it’s always crucial when making a point to build upon a strong foundation from which to elevate.

Writers and performers have been breaking characters into quantifiable types and purposes long before film was even invented. Once fleshed out, characters are the driving force that evolves ideas into a full-fledged story. The characters shape everything in a script, and every one of the five possible specific purposes they serve illuminates how the story unfolds. This article will look closely at the most principal role of the five major characters.

The protagonist is the character through which the author takes the audience on an exploration of a premise, theme and central question. All characters stem from the premise; a deeply rooted point that the writer wants to make or explore with the script. Often called the hero or heroine, even if his or her actions are not necessarily heroic, this is the character through whose eyes the writer tells the story and makes the point they are trying to extol. Every other character in the story is built and designed to challenge your protagonist in specific and unique ways. In short, using the solar system as an analogy, premise is the sun at the center of the universe around which your protagonist revolves while other characters revolve around him or her like moons.

There are two journeys a protagonist takes during a traditional, cinematic story:

- The outer journey (a physical mission, goal or task), which the hero sets out on by the end of act one, and

- The inner journey (character arc) initiated from page one in the form of the personality or character flaw with which your protagonist starts the story.

Let's talk about how these journeys are told. Passive protagonists are frowned upon by the industry (and quite frankly, boring as hell). Therefore, these characters should be proactive. It’s crucial he or she faces constant confrontation, which requires making tough decisions and taking action. They may make bad choices and take the wrong actions fueled by the personal character flaw. It is this deeply human shortcoming (which should directly reflect the premise and central question of the story) that gives the hero their depth and humanity. Human imperfection provides the opportunity for empathy from the viewer, since we all make mistakes. Without a flaw, the protagonist simply does not feel realistic. After all, nobody is perfect, therefore, neither is your protagonist. Like real people, they are a work-in-progress.

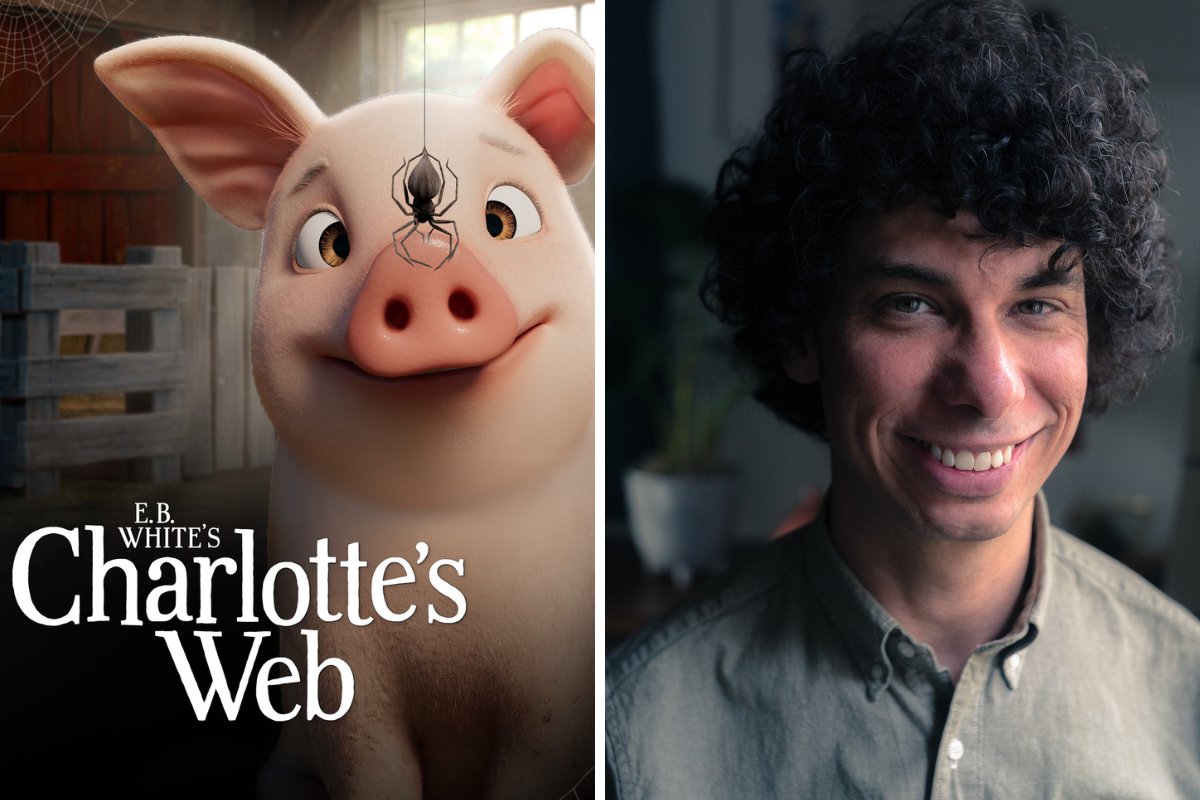

A bright writer introduces his or her protagonist through an easily comprehensible, normal situation an audience can identify with, often starting from the most mundane of possibilities (even in the most fantastic of stories). It is common to begin with a protagonist that truly appears average (but has personality). For example, let’s look at the wild worlds of fantasy and science-fiction, blockbuster classics, Star Wars and Harry Potter. It boggles the mind to think of all the possible wild, outlandish lifestyles they could have chosen for the protagonists in these universes. Yet, for such fantastic realities, their origins are anything but. Luke Skywalker starts his journey as a simple farm boy that wants to go off to the academy (college) with his pals, but he has to stay on the farm to help his Aunt and Uncle. Harry Potter starts even lower, forced to sleep in the closet under the staircase. It’s not a coincidence that Harry and Luke were both orphans, which helps build sympathy for the central characters. This is done on purpose so that the typical audience member (who is in the dark about such things as The Force or Hogwarts when they enter the movie theater) can experience shock and awe of all the imaginative things to come in tandem with the heroes. This puts the audience directly in the protagonist's shoes.

It's no wonder Dorothy Gale's story begins on a small farm in Kansas before the tornado sweeps her off to Oz. Humble beginnings help each escalation, reveal and new experience have greater impact on the protagonist (and the audience in his or her shoes). Through innocent, humble eyes, the protagonist's breath can be swept away. Genuine awe is the greatest emotion to create in characters, and that awe felt by the protagonist translates directly to the audience if they share the same perspective. It allows the writer to generate visceral and emotional responses in protagonists with which the audience can empathize as they experience world-changing events. This makes for a truly visual and emotionally dynamic rising action, one scene at a time.

Every scene in the script is about the protagonist’s two journeys, even if that character is not in the scene. Meanwhile, the impact of these events that shape the hero’s journeys should become so intense that it triggers a major change in the heart of the protagonist and changes him or her forever. That change is called the character arc (or “character curve” in the original stage version of the concept). This arc stems directly from the character flaw. Most great protagonists have and overcome them, with the rare exception. For example, Forrest Gump is a story in which the world is flawed and changing constantly around a character that remains constant.

Before we conclude our first blog on the first of five character models, we should address the one last potential version on the protagonist known as the antihero. Wikipedia defines the term, “The antihero or antiheroine is a leading character in a film, book or play who lacks some or all of the traditional heroic qualities, such as altruism, idealism, courage, nobility, fortitude, and moral goodness.” In short, they can be a total jackass (Bad Grandpa), idiot (The Jerk), drug-dealer (Scarface), drug addled (Inherent Vice), pimp (Hustle and Flow), gigolo (Midnight Cowboy), hitman (Pulp Fiction), thief (The Thomas Crown Affair), dirty cop (Bad Lieutenant), egomaniac (Citizen Kane), sociopath (Nightcrawler), mob enforcer (Get Shorty), bank robber (Dog Day Afternoon), con artist (The Sting), convicted criminal (Cool Hand Luke), porn star (Boogie Nights), gangster (Goodfellas), the worst kind of despicable lawyer (Liar, Liar), sleazebag father whose sole purpose it is to sleep with his high school teenage daughter’s pretty friend (American Beauty), split personality terrorist (Fight Club), with a wide range from a highfalutin, multi-millionaire, stock-trader (Wolf ofWall Street) to the lowly and unimpressive, adult, useless, lay-about slacker (The Big Lebowski). Now, the protagonists are all supposed to have flaws… But these are more major than one might expect. The history of cinema is filled with protagonists with human qualities and jobs that no reasonable, logical person would think should carry the role of a film’s hero or heroine. How do writers get away with this?

A character’s point of view (POV), which is where personality meets perspective, can bridge the shocking gap between the character we would normally see ourselves rooting for and the protagonist in the story. Through POV, the writer must find a common ground rooted in the nasty attributes of an antihero, and an everyday moviegoer responsible and good enough to pay for movie tickets in this age of digital piracy and BitTorrents. So, the writer takes the character-designing concept of generating a personality flaw that makes a character believable to the audience as a real person… And reverses the math on it.

Now, instead of looking for a flaw to insert into a hero, the writer searches for the right redeemable quality to plug into an extremely flawed protagonist. These can include attributes that build sympathetic, empathetic, and endearing respectability through a personal moral code or duty that engages us enough to suck us in as story lovers. They share a common goal with that of someone you would associate with being heroic. This elevates the character beyond their disreputable outward qualities. Traditionally the “anti” in antihero has to do with how the protagonist takes action. Either they do bad actions with some type of moral code (like criminals, killers, conmen, or womanizers), or they do upstanding deeds with a lousy POV (think shallow lawyers, habitual liars, total jerks, and extremely offensive characters like racists). By today’s standards, Huckleberry Finn would be an antihero.

In short, from the outside, the antihero takes actions that do not fall within the Judeo-Christian understanding of moral boundaries and good, law-bidding behavior, but there is something we see inside them that makes the morally corrupt redeemable in some way. The Professional is a contract killer that spends the movie trying to save an innocent, little girl that witnessed a murder. Dirk Diggler in Boogie Nights is desperately looking for the love and belonging of family, which he never had, only to find it in the San Fernando Valley’s pornography industry. Sonny Wortzik in Dog Day Afternoon robs the bank in order to get his desperate, gay lover the sex change operation he cannot afford. So outwardly, they do bad things, but their motivations allow us to empathize with even the most unlikely of protagonists. They tether themselves to us, engage us, and endear us to the antihero through sympathy, unique moral code, or a goal that is entertaining and engaging enough to suck in us story lovers.

Today, you read about the first and most central of the five major character types in modern storytelling, the protagonist. This was the basic foundation necessary to fully understand all the other character purposes as this column progresses. Our next article explores the character audiences love to hate… The Antagonist.

- More articles by Michael Tabb

- Rewrite: Tips for Strengthening Your Protagonist's Aim by Paul Chitlik

- FREE Creating Dynamic Characters Webinar

Get amazing advice on inner and outer journeys with Chris Vogler and Michael Hauge's DVD

The Hero's Two Journeys

Michael Tabb is a firm believer in giving back to fellow artists in an ongoing effort to constantly elevate the medium of visual storytelling through the exchange of free-flowing ideas. This column is one WGA writer’s perspective of entertainment from within the screenwriting trade, including craft as well as industry, occasionally separating conceptions from misconceptions. It’s part trade analyses and part opinion column. Writers are story surgeons. Scrub in and let’s dissect this living, breathing, evolving thing we do called entertainment writing. Read the book inspired by Michael's articles at Script Magazine Prewriting Your Screenplay: A Step-By-Step Guide to Generating Stories, and follow him on Twitter: @MichaelTabb, Instagram: @MichaelTabbWGA, and Pinterest.