Love, Loss, and the Afterlife We Build: A Conversation with ‘Eternity’ Director David Freyne

Writer-director David Freyne on balancing whimsy, grief, and the quiet radicalism of ordinary love in ‘Eternity’.

There are films that unfold like poems and films that unfold like equations. Eternity, directed by David Freyne and co-written with Pat Cunnane, is one that unfolds like a memory, vivid, inexplicable, playful, and achingly real. From its arrival in a pastel-tinted afterlife junction bursting with absurdity to its quiet closing moments of belonging, Freyne’s latest is a rare romantic comedy with the conceptual confidence of a philosophical meditation and the emotional clarity of a lived experience.

In a cinematic landscape where stories about death often veer toward spectacle or abstraction, Eternity stands apart by treating the afterlife not as a puzzle to be solved but as an emotional playground. Souls arrive, baggage and all, to choose where they will spend forever. The rules are simple, the stakes feel immense, and the result is a story that feels both deeply humane and quietly audacious.

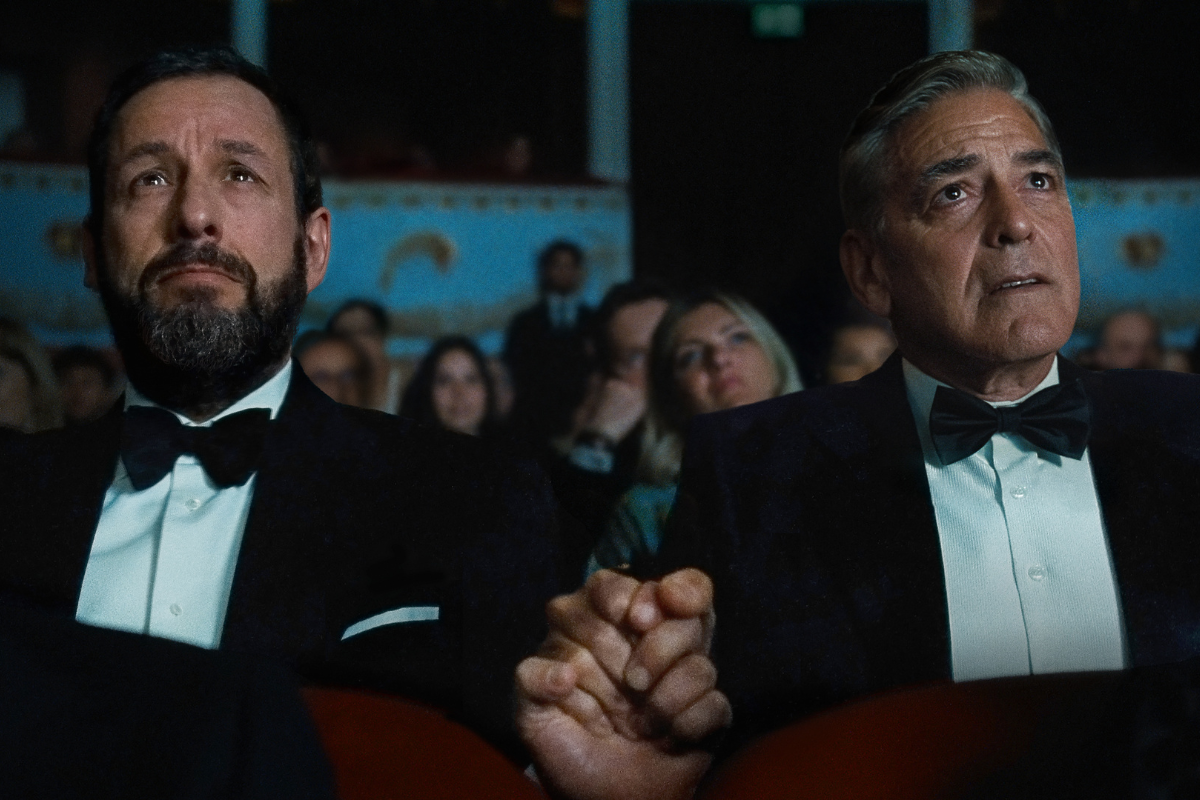

At the center is Joan, played with luminous warmth by Elizabeth Olsen, a woman who has lived a long life and must now choose between two loves: Luke, her first love who died young, and Larry, the partner who stayed with her for decades. The premise could have easily collapsed under its own cleverness, but under Freyne’s steady and empathetic direction, it becomes a profound question about memory, desire, identity, and the three-dimensional shape of love itself.

When I first watched Eternity, what struck me most was how effortlessly its whimsical world and emotional heartbeat coexisted. The afterlife here is bureaucratic and busy, echoing the everyday madness of life rather than the solemn grandeur of heaven. Beneath the humor and vivid production design, there is an honesty that feels instantly recognizable and deeply resonant.

In our conversation below, David Freyne talks about tonal balance, building an afterlife that feels viscerally human, guiding actors through decades of emotional history, and why a film about endings can be one of the most life-affirming experiences a filmmaker can make.

Rahul Menon: Eternity feels both whimsical and deeply human, a film that lets audiences laugh and then quietly blindsides them with emotional truth. You’ve spoken about wanting to capture both hilarity and heartbreak in the same breath. How did you find that tonal balance without letting the afterlife setting become too sentimental or too absurd?

David Freyne: I just feel like life is a balance between comedy and heartbreak. I don’t think they’re ever too far away from each other. Reflecting that in my work felt essential because that’s where the greatest emotional truths live. Always coming back to that essence and to our characters helped keep the film grounded, no matter how fantastical the world around them became.

Rahul: In my review, I wrote about how deeply the film respects the “ordinary love” between Joan and Larry, not flashy, but lived in, layered, and earned. Was there a moment during development or rewriting when you recognized that relationship as the emotional spine of the story?

David: That was always the core for both Pat Cunnane and myself. We both reflected so much on our own lives in writing this, and I think it was those everyday moments that really speak to us. We always went back to our opening scene of older Joan and Larry bickering in the car. The simple ease they have with each other felt so honest and set the emotional tenor for the whole film.

Rahul: You’ve talked openly about how much you enjoyed thinking about love over the four years you spent making this. Were there conversations with Pat or with the cast that shifted your own definition of love as you worked?

David: Absolutely. For all of us, it was important that the film could celebrate many kinds of love, young love, enduring love, and even choosing yourself, like Karen does. Love and happiness can come in so many different forms, so trying to define it rigidly felt untruthful. I think the one unifying feeling for all of us is that you can experience so many different loves in your life, and what that is can change over time too. I never want Joan’s choice to be seen as right or wrong. It’s just the one that reflects who she is now.

What becomes clear early in Freyne’s answers is that Eternity was never interested in ranking loves or crowning one version as “correct.” Instead, the film treats love as something elastic, shaped by time, memory, and circumstance. That generosity of perspective is what allows the film to feel emotionally radical without ever raising its voice.

Rahul: The afterlife junction is one of the most memorable production design choices in recent cinema. When you first imagined that world, what did you want audiences to feel when they arrived there?

David: I wanted them to experience the madness through Larry’s eyes, the chaos and frenzy of all these desperate vendors hawking their various eternities. But I also think, and it’s something we discussed a lot, that there is comfort in the chaos of the junction. It’s bureaucratic and frustrating, just like the world we live in. We spend so much of this film exploring the idea that all we are is a collection of our memories. Da’Vine’s Anna says a soul is just you, if you were annoyed a lot in life, you’ll be annoyed a lot in death. There is this idea that the afterlife might be celestial, but I truly believe that if there is an afterlife, then it can’t be that serene because, well, we’re there. We’ll bring our neuroses and anxieties with us to corrupt it.

Rahul: You’ve cited A Matter of Life and Death and The Apartment as touchstones in shaping the film’s emotional DNA. What did those films teach you about sincerity, especially in stories about death, longing, and impossible choices?

David: They’re different films, but both are deeply romantic in their own way. They reflect second chances at life and love in a way I find profoundly moving and sincere. At the risk of being saccharine, you can find light in the darkest moments, whether that be at war, as with A Matter of Life and Death, or after a suicide attempt, as with The Apartment. And I think that rings true to Eternity too. I always say Powell and Pressburger are the visual inspiration while Wilder is the tonal one.

Rahul: Your leads bring such a rare blend of comedy and drama to their roles. Were there moments during performance or rehearsal that reshaped how you saw their characters?

David: It was really the work I did with them in development that had the biggest impact on the script. They had so much insight into the characters that I couldn’t help but make so many small changes in response to them. They never once asked for a script change, but I was just so inspired by them. Miles was always talking about how much he loved the ways Larry tries to make Joan happy, which inspired me to write the squatting scene, which I think is one of the most romantic moments ever. Lizzie really hit on the truth that Joan had never truly made a choice that was entirely about her, which she then ends up saying while drunkenly lying in the Pearly Gates: The Classic Edition booth.

In production, it was the small gestures and breaths that so surprised me. Callum sliding peanuts to Miles. Miles hiding a pretzel in his pocket. Tiny moments that so enriched the characters.

That sense of lived-in spontaneity is one of Eternity’s quiet triumphs. Even within a meticulously designed afterlife, Freyne and Cunnane allow human behavior, awkward, funny, impulsive, to punch through the artifice. The result is a world that feels imagined yet oddly familiar, elevated yet emotionally accessible.

Rahul: Joan’s emotional history is fully intact inside her younger body. How did you guide Elizabeth Olsen to portray that depth, the sense of nine decades lived, without relying on obvious physical cues?

David: We spoke about people we knew and how we’ve seen them change over time. How posture and voices change with age. Not just the physical effect of aging, but the emotional effect of it. But all credit to Lizzie. She really did the work. I mostly love how she could move from old to young depending on who she was with. We both really felt that Joan is a different person with each man. Within the same scene, you can almost feel her shed her years as she turns from Larry to Luke. It’s incredible. The idea that it’s not just a choice between Luke and Larry, but a choice between two very different versions of herself that reflect different times in her life.

Rahul: Many films about the afterlife lean into satire, but Eternity uses it to ask something more honest: what truly makes us happy? When creating worlds like the man-free or fake Paris, did you ever find yourself tempted by any of them?

David: I wanted each world to have a kernel of truth behind it, no matter how absurd. I mean, a Queer World where straight people aren’t allowed is a joke, but there was definitely a time in my life when I would have wanted that, when the world felt like an unsafe place for me.

I also love how we romanticize things. When we imagine living in an Austen-esque England or medieval times, we don’t factor in that everything will smell because they don’t have modern toilets. So, the idea of getting these revisionist worlds to choose from, like Medieval World with Modern Plumbing or Weimar Germany without the Nazis, were both really funny and incredibly appealing.

Rahul: The chemistry between the trio is breathtakingly delicate. Was there a moment in pre-production or early rehearsals when you knew the triangle would sing?

David: Honestly, the nervous energy stays with you right up to set. We had done some rehearsals in groups of two, but it wasn’t until set that we got them all together. We made sure to film all the archive tunnel scenes first, which became a nice extension of rehearsal where they got to play the past moments in these relationships and fill in those gaps. That’s also when Miles and Callum first met, and they got on so well. That was the moment I knew it would be great. They were the missing relationship in this trio, and the fact that they had such instant chemistry made me instantly relax.

One of Eternity’s greatest achievements is how it refuses to villainize desire. No one here is wrong for wanting what they want. Freyne’s film understands that longing is not betrayal. It is memory insisting on being heard.

Rahul: You’ve said this film made you less scared of death. Was there a scene or line that felt especially personal or therapeutic for you?

David: Joan says, “The beauty in life is that things end.” The idea that the finality of life is what gives it meaning. That has had a big impact on me, but it’s really in the last eight months that I’ve realized quite how profound an impact. I’ve been open about the fact that I’ve been quite ill. I’ve had to deal with a stubbornly large brain tumor. There were several months when it didn’t seem like I would see this year through. But Lizzie’s voice was in my head just saying that line, almost like a mantra, and it made me feel less scared of what I was facing.

Rahul: The ending celebrates small, grounded happiness rather than grand romantic gestures. Were you ever tempted to lean into something more traditionally romantic?

David: I think the honesty and gentleness of the ending are what make it truly romantic. Miles and Lizzie are so delicate in that moment. It will always make me tear up. There’s a subtle courage in restraint, and that felt truer to the story than any grand gesture. They do walk off into the sunset, though. That’s as classically romantic as you can get.

Rahul: Da’Vine Joy Randolph and John Early bring so much humor, yet their quiet walk in the waking junction is one of the film’s stillest moments. What inspired that choice?

David: I wrote that scene just a few days before we shot it. It’s a moment in the film that we needed, a breath, but I just loved working with them so much and wanted them to have a scene alone where these characters question their roles in this afterlife.

Originally, it was to be them perched on the edge of the junction like the angels in Wings of Desire that are on top of the Siegessäule statue. I realized them walking into this junction as it wakes up and people hoover was more in keeping with the language of our film and more powerful in its simplicity.

It’s one of the most stunning shots in the film to me.

For a film bursting with ideas, Eternity knows when to stop talking and simply listen. Its most profound moments often arrive in silence, a glance, a pause, a walk shared between two people who suddenly understand something they didn’t before.

Rahul: You mentioned Vancouver’s surrounding mountains and how deeply you miss your cast and crew. If you could bottle one moment from set, a single day or tiny exchange, and keep it forever, which would you choose?

David: The day we shot Joan’s arrival was electric. Having all five leads and over 100 extras in a giant set that only existed in my head a few months earlier was a true pinch-me moment. But I truly loved every day of my time there. That cast and crew have burrowed into my heart, like a cuddly form of heart disease.

Rahul: Eternity deals with love, loss, and choice, but it also quietly speaks about identity, who we were, who we became, and who we wish we could return to. Were there any personal anchors or memories you kept revisiting while shaping Joan’s emotional journey?

David: There are so many for me, and I know Lizzie had her own. As I said before, I always went back to the opening. The comfort of an older couple who can just bicker and be themselves. The ease they have with each other epitomizes love for me. Lizzie always says Larry choking on a pretzel is when she fell in love with him because she could so easily imagine her husband going that way.

Rahul: Now that Eternity is out in the world, what do you hope a young filmmaker watching it years from now takes away from it?

David: I mean, it would be just incredible to think someone will find it in 20 years. That’s the dream. I firstly hope they enjoy it and don’t feel the work. I always think the hard work is in concealing the effort, particularly with comedy or romantic comedy. It should feel effortless.

If it inspires them to dream up their own idea of the afterlife, that would be lovely too.

Rahul: Stepping back from this film, who are some writers or filmmakers who’ve shaped how you think about storytelling? Is there one influence you feel yourself returning to again and again?

David: I've harped on a lot about Powell and Pressburger. Billy Wilder and Ernst Lubitsch, I love their work. The Coen Brothers, Wim Wenders, Rob Reiner, and John Waters are icons to me. Greta Gerwig is incredible. I am in awe of her work. I love Andrew Haigh. I like all his work, but I think Weekend and All of Us Strangers are perfect films.

The director I return to again and again is Alexander Payne. His balance of comedy and drama, the economy of his stories, the way he slowly reveals his characters. It’s all just a masterclass in storytelling.

Rahul: As you look ahead, what kind of filmmaker do you hope to grow into after making Eternity? Is there something you feel newly brave enough to try after making Eternity?

David: There are so many genres that I would love to explore, but I just want to continue to tell stories that mean something to me and hopefully reflect me in some way. I think there is bravery in being able to be vulnerable when making something.

Eternity does not answer the mysteries of death. It offers something quieter and far more generous, a space where love is not perfected but understood. What lingers long after the credits is not the fantasy of forever, but the pulse of connection that makes life, and cinema, worth returning to again and again.