Thoughts on ‘Killers of the Flower Moon,’ Ethical Storytelling, and Writing Characters Unlike Yourself

What does authentic, ethical storytelling mean?

Writers have immense power. We might not often consider that, but we do. I’m not just talking about how we create whole worlds and characters. We also influence people’s thoughts and worldviews, whether we intend that or not.

“[T]he protagonist is never in control. Only the narrator is,” writes Emily Fox Kaplan in Guernica, referring to a deeply personal story but speaking for so many more. Even in nonfiction, the storyteller is the one who frames history, the one who holds all the cards.

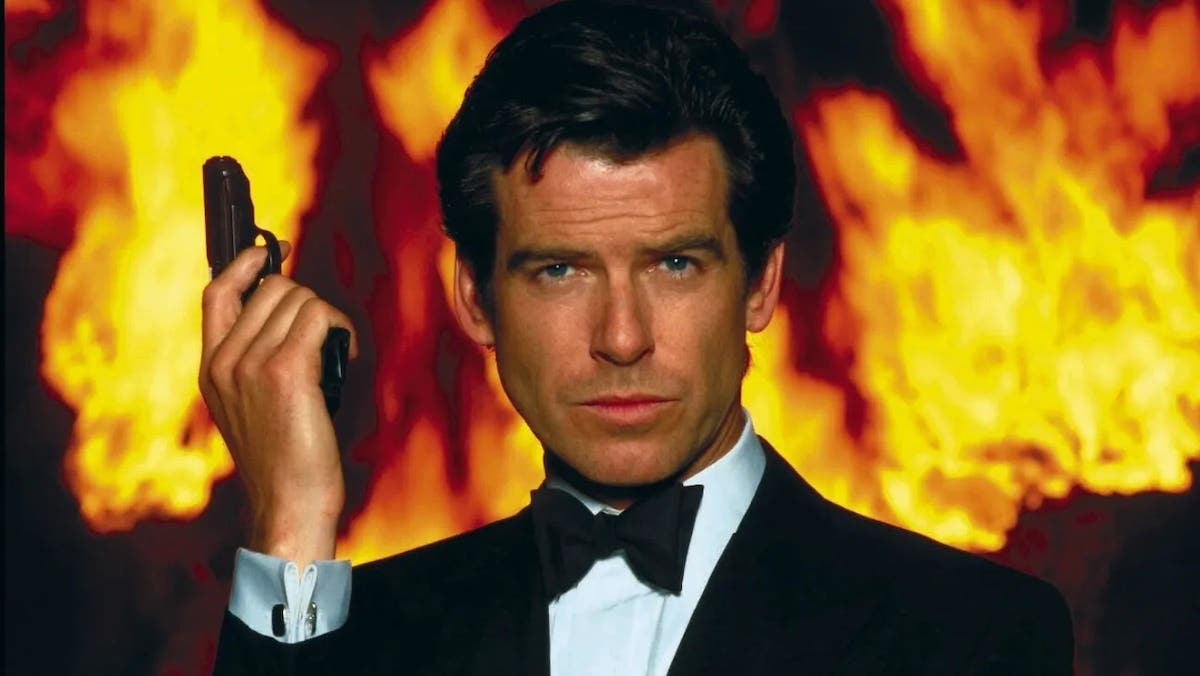

Telling stories authentically has been on my mind a lot this month, thanks to the debut of director Martin Scorsese’s latest film, Killers of the Flower Moon, and writers’ ongoing struggle with telling stories and creating characters unlike ourselves.

What does authentic, ethical storytelling mean? It presents diverse viewpoints responsibly, conveying emotional truth and experience—not regurgitating tired tropes, cliches, and stereotypes.

Ethical Engagement

Sunny Singh, an author and professor of creative writing and inclusion in the arts at London Metropolitan University in the United Kingdom, calls this ethical engagement: being as truthful as possible to the experience of someone different from us without causing additional harm to people often marginalized.

“The way [writers] inhabit the world is not necessarily the way their characters inhabit the world. Just being aware of that and thinking about it. … It’s not rocket science. It’s just awareness,” Singh said, speaking via Zoom this month on the writing blog Bang2Write.

Scorsese in various interviews shows such awareness in discussing his adaptation of author David Grann’s 2017 best-selling book Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI. The book is a detailed, researched narrative about what the Osage Nation calls the Reign of Terror. Oil discovered on their Oklahoma land made them the richest people per capita on Earth by the early twentieth century—and the target of whites conniving to steal their wealth. Dozens of Osage people died during those years, some shot or otherwise killed; several were married to white spouses who obtained their land rights upon their deaths.

The book frames the story around the federal investigation that uncovered a vast conspiracy among the killers and others who simply looked the other way. This made Scorsese uncomfortable.

“After a certain point, I realized I was making a movie about all the white guys,” he told TIME. “Meaning I was taking the approach from the outside in, which concerned me.”

The filmmaker, who co-wrote the screenplay with Eric Roth (Dune), also thought an audience wouldn’t find much suspense in that. “They know it’s not a whodunit; it’s who didn’t do it,” he’s said.

Scorsese met with Geoffrey Standing Bear, principal chief of the Osage Nation, to discuss what drew him to this story and hear the Osage’s concerns about the project. As a result, the film incorporated the Osage language and customs, with many Osage people advising the filmmakers.

The film also recentered the narrative around Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), a real-life World War I infantry cook who married Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone), a wealthy Osage woman. The onscreen Ernest is dim and lazy but seems to love Mollie, calling her “a lady”; yet he also plots with his cattle-baron uncle Bill Hale (Robert De Niro) to kill at least one of her three sisters. Meanwhile, another sister and her mother (Tantoo Cardinal) die from a mysterious “wasting illness” while Mollie, a diabetic, grows weaker.

Although Chief Standing Bear gave the finished film his blessing, the film has stirred complicated feelings in some participants and viewers. Christopher Cote, an Osage language consultant on the project, said he thought the film presented the Osage culture respectfully but was troubled by the heavy focus on Ernest and the conspirators.

“As an Osage, I really wanted this to be from the perspective of Mollie and what her family experienced, but I think it would take an Osage to do that,” he’s said. “I think that’s because this film isn’t made for an Osage audience; it was made for everybody, not Osage.”

Devery Jacobs, who stars on Reservation Dogs, praised Gladstone’s performance, saying she “carried Mollie with tremendous grace,” but said other Osage characters were “painfully underwritten” as “helpless victims without agency.”

“Authenticity Checks” Elevate Marginalized Views

In my review of the film, I wrote that I also wanted to know more about Mollie, how much she suspected, what compromises she knew she made. Early in Killers of the Flower Moon, she calls Ernest a “coyote.” She knows he likes money. But she didn’t arrange with him for her relatives and so many in her community to die.

As I read about Scorsese’s outreach and respect for the Osage, I kept bumping into the fact that he’s still told a story mainly about white guys—albeit not the “white saviors” of law enforcement but the villains. As The New Yorker’s Anthony Lane put it, “Although its moral ambition is to honor the tribulations of an Indigenous people, it keeps getting pulled back into the orbit—emotional, social, and eventually legal—of white men.”

Get Real: How Barbie’s Emotions Build a Transformative Journey

Yet Scorsese might have a broader reason for that. Now in theaters and soon on Apple TV+, Killers of the Flower Moon is an epic film, a reckoning with manifest destiny and white supremacy as well as a metaphor for the betrayal and mistreatment of indigenous people. Audiences can use this story to think of their own complicity in racism. “[T]hat’s the fear: that maybe we’re all capable of this sort of thing,” Scorsese has said.

One hopes that the high profile of Killers of the Flower Moon elevates more unheard voices and inspires screenwriters to tell these stories.

One way to do that ethically is through sensitivity reads, or what one of my clients calls “cultural research reads.” This idea is a hot button for some creatives who object to this on principle, likening their input to “wokeness” or what author Ian McEwan (Atonement) in The Guardian this month called “mass hysterias.”

Granted, some readers can provide lousy feedback, just like some writers can produce lousy stories. But conscientious readers aren’t out to squash someone’s creativity, said Lucy V. Hay, a script reader in the UK for two decades who also is a script editor, author, producer, and blogger hosting the Bang2Write online community. (I’m part of that group and have taken classes from her.)

Rather, these “authenticity checks,” as Hay calls them, identify areas that are stereotypical compared to one’s lived experience and offer suggestions to enhance a story. She provides notes related to the portrayals of female characters, queer characters, mental illness, and other issues. She’s also asked for such feedback, such as when writing about trans youth in her 2017 novel The Other Twin (published under the name LV Hay).

Irvine Welsh, author of Trainspotting, told Sky News that he likewise found the feedback of trans readers “absolutely brilliant” when writing his 2022 book The Long Knives, which includes trans characters. At first, he said, he thought, “I’m not gonna like this at all. This is, like, censorship.”

But their comments made him realize that “I completely had the wrong end of the stick, basically. They wanted to make the book as good and as authentic as possible. They were incredibly supportive,” he said. “What you don’t want to do is write something that is hurtful or wounding to people and is misrepresenting them.”

Taking Inspiration from the Setups and Payoffs of 'Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3'

No one is saying that white writers, straight writers, wealthy writers, and so on can’t write people who aren’t like them, Singh added. “I would like white writers to actually write characters of color well … to create characters that are not dehumanized. That are not exoticized. That are not fetishized. To me, that is part of the craft of writing,” she said.

The problem she encounters is when writers create a character who is, say, a South Asian woman like Singh, who was born in India, but bases this on a friend or relative who is South Asian. No one person represents an entire community.

Go Beyond Your Worldview

When creating characters different from yourself, research is invaluable. If you’re writing South Asian characters, for instance, Singh recommends reading work by South Asian writers to familiarize yourself with different issues and concerns, as well as annoying tropes.

Ask yourself: “Is it the way I think it is?” Hay said. “Sometimes we can get so caught up in our own opinion that we’re actually projecting it.”

Try writing exercises that encourage thinking beyond your worldview. Singh tells her undergrads to imagine they’re a woman who stayed late at the pub and has two ways to walk home alone: a shortcut through a dark alley that takes five minutes, or a well-lit stretch that takes about fifteen to twenty minutes. Most male students will have her take the shortcut, she said. “Every woman will be like, ‘Yeah, not taking the alley.’”

Here’s another exercise from Singh: When creating a character different from you, make a list of any aspect that’s unlike you. Then note every cliché or stereotype about those aspects—and avoid them. (You can subvert the familiarity of ideas we’ve seen before, as long as you do so in a way that’s not offensive, boring, or stale, Hay added.)

Seek out script readers and consultants with relevant lived experience. Hay also likes Salt and Sage Books, an editorial company that provides sensitivity reads and publishes guides about writing characters who are Black, autistic, asexual, or have experienced sexual assault. In addition, the company offers webinars about native representation, gender identity, and neurodiverse representation in literature.

Aim in your writing to know better, so you can do better, Singh said, paraphrasing literary activist and icon Maya Angelou.

Lastly, be humble and open to the process of discovery. “We don’t know what we don’t know,” Hay said. “Writers will recycle the same bullshit ideas unless we really sit down and challenge ourselves on the prejudice and biases that we all have.”

Learn more about the craft and business of screenwriting and television writing from our Script University courses!

Valerie Kalfrin is an award-winning crime journalist turned essayist, film critic, screenwriter, script reader, and emerging script consultant. She writes for RogerEbert.com, In Their Own League, The Hollywood Reporter, The Script Lab, The Guardian, Film Racket, Bright Wall/Dark Room, ScreenCraft, and other outlets. A moderator of the Tampa-area writing group Screenwriters of Tomorrow, she’s available for story consultation, writing assignments, sensitivity reads, coverage, and collaboration. Find her at valeriekalfrin.com or on Twitter @valeriekalfrin.