STORYTELLING STRATEGIES: “McFarland USA”‘s Approach

Paul Joseph Gulino discusses three problems with the idea of the end of the second act always being a “low point.”

Paul Joseph Gulino is an award-winning screenwriter and playwright, whose book, Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach has been adopted as a textbook at universities around the globe.

The end of the second act isn’t always a “low point.”

It’s common to hear the assertion that the end of the second act is the “low point” or the “all is lost” moment in a screenplay. Blake Snyder argues for a “Dark Night of the Soul” beat, which in turn follows the “All is Lost” beat, just before the third act.

In today's Storytelling Strategies, there are three problems with this idea in terms of story development...

- A great many successful films simply do not follow this pattern.

- Adhering to this idea can limit the imagination, and thus the possibilities of the story, which leads to three...

- Predictability.

A case in point in how to avoid this trap can be seen in McFarland, USA. (Disclosure: this film was co-written by my colleague Bettina Gilois).

The Sports Movie and Predictability

Movies about athletic endeavors, particularly those based on real stories, tend to be a challenge because sports outcomes are binary—either your team (or player) wins or loses. And if it’s based on a real story, most likely the outcome will be positive. No one makes a movie about a team that did halfway decent.

Correspondingly, it makes sense that, in telling such a story, the third act will be the final contest and victory, and because cinema needs contrast to create an impact, the end of the second act will be a moment where we believe there is little or no chance of victory: a low point.

Such a structure can certainly enhance the experience of the final contest, and leave the audience fulfilled, but it also runs that risk of predictability. If we reach a point where all seems lost, we can pretty much fill in the blanks about what the outcome will eventually be.

Mixing Things Up

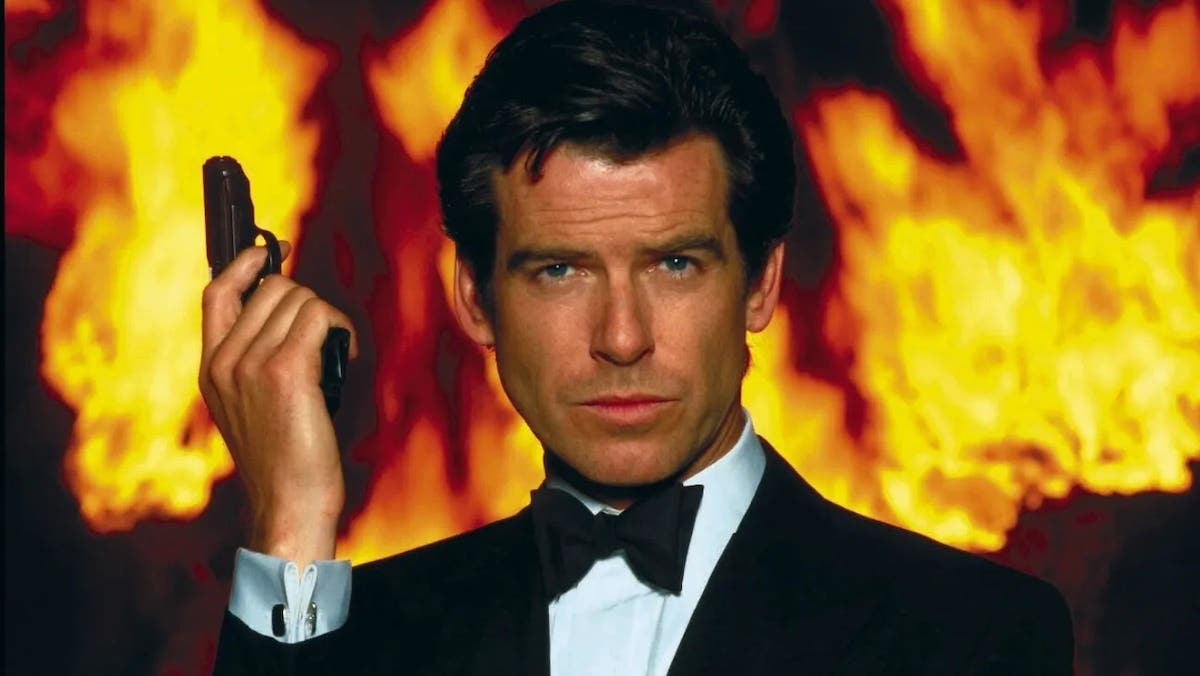

McFarland’s story surely risks predictability. A new coach, Jim White (Kevin Costner), discovers the innate running ability of a group of poor boys in a poor rural town and establishes a cross-country team. The goal of the team (making it to the state championships) is held forth, providing a deadline that helps to frame the movie (i.e., the movie will likely be over shortly after the state championships).

The state championship goal also provides the main dramatic question that creates the main tension of the film: will the team win the championship? The problem for the storytellers, meanwhile, is how to avoid predictability in a story centered around a win or lose question.

The solution in this case is the introduction of another element to the story, a secondary objective for the main character (Jim White): escaping the town for a more lucrative and satisfying job.

The film begins with White being fired from a coaching position in Idaho and arriving in rural, impoverished McFarland, California, as a last resort: he has no other options for employment, and must support his wife and children. Thus this secondary objective--the family enduring the town of McFarland until White can find another job--is established early.

The Low Point

Naturally, the low point in McFarland, USA might hypothetically be contrived like this: just before the state championships, the team’s star runner is expelled from school for getting into a fight while defending a friend in a hallway, and is thus unable to compete. Or a couple of key runners are injured. Or forced off the team for academic reasons. Or the coach is fired for budgetary reasons. Or due to a rival at the school who engineers a scandal against him. The coach’s dark night of the soul could thus occur while he broods about what might have been. Or maybe the dark night of the soul belongs to the players who contemplate how close they came, and now they have to go back to picking vegetables with nothing to show for their efforts.

Fortunately, the storytellers of McFarland chose none of these. In fact, just before the state championships (the end of the second act), the players, coming off a qualifying round victory, get new uniforms. No dark night of the soul here.

However, there is a very disturbing moment that occurs shortly thereafter: White’s daughter Julie (Morgan Saylor) narrowly escapes harm after an ambush by a local gang. This crisis has no direct bearing on the team and its prospects in the state championships, but it does impact directly the secondary question of Coach White’s plans to leave the town for a better job because it provides an added motivation: his family's well-being is at stake.

The stage is thus set for a less predictable third act, because now, looming large over the final race, is the prospect that the team will lose its beloved, inspiring coach, and he and his family will see the web of close relationships they have established in the town sundered.

This question dangles throughout the third act and is sustained until after the team has won its championship, when we finally find out that White has decided to stay despite a much more lucrative offer elsewhere.

The team’s ultimate victory is a given; the coach’s decision, less so.

Glory Road

Screenwriter Gilois also wrote the script for a previous Disney sports-oriented film, 2006’s Glory Road, which provides a useful comparison. Like McFarland, Glory Roadis based on a real story about underdogs, in this case the unheralded and undervalued basketball team of the Texas Western College during the mid-1960s.

The bulk of the picture portrays the remarkable 1966 season, in which newly-hired coach Don Haskins (Josh Lucas) recruits African-American players because his school doesn’t have the budget or prestige to attract top-notch white players. The move is unprecedented in a southern college in the 1960s, but Haskins’ desire to win trumps his fealty to racist tradition: the African-American players make his team competitive.

The third act—i.e., the last 25% of the film—concerns the national championship games. Just before this, the expected “low point” occurs, and in this case—unlike McFarland—it does relate directly to the main question of whether or not the team will win the championship: the players, rent by internal division and external racist threats, lose a game and thus their undefeated season. The chance of winning the championship is in serious doubt.

Screenwriter Gilois escapes the predictability trap, though, by bringing forward in the third act another element integral to the story: the persistent racist harassment of the African-American players. On the eve of the championship game, Coach Haskins, who till now has only been concerned with winning, decides to make a broader, more important statement. He tells his team he plans only to play the black players, even if it costs them the game.

The third act thus proceeds with considerably more heft than it would have if the only concern had remained the binary win or lose question.

Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis

The most fruitful way to think about the end of the second act is not to see it as a “low point” that must be engineered whether or not it grows naturally from the story, but rather as a resolution, or partial resolution, of the main dramatic question, leading to a fresh problem or tension not hitherto foreseen.

When confronted with a binary question, it’s fine to dangle the two possible outcomes—A or B—in front of the audience for the second act, but in the third act it’s best to challenge yourself to come up neither A or B but rather C—an unexpected and preferably broader, deeper solution to the problem the screenplay poses.

- More Storytelling Strategies by Paul Gulino

- The Third Act by Drew Yanno

- What is a Story: Plot – What Happens Next?

Beginning Feature Film Writing: Act II & III

Avoid Losing Momentum After Your First Act With Feedback and Guidance From an Industry Pro

Learn Valuable Techniques That Will Ensure Your Audience is Riveted Through the Last Two Acts

Empower Yourself to Power Through the Second (and Third) Acts Without Getting Stuck

Paul Joseph Gulino is an award winning screenwriter and playwright, whose credits include two produced screenplays in addition to numerous commissioned works and script consultations, and his plays have been produced in New York and Los Angeles. He taught screenwriting at the University of Southern California for five years, and since 1998 has taught at Chapman University in Orange, California where he is an associate professor. He has lectured and given workshops in the U.S. and Europe and recently guest-lectured at Disney Animation in Burbank. His books include Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach and The Science of Screenwriting: the Neuroscience Behind Storytelling Strategies, co-written with psychology professor Connie Shears. His web site is www.writesequence.com.