Breaking & Entering: Pizza Is The Key Part 4 – Devices Add Flavor But Don’t Bury Your Story

Hungry to create a story that really delivers? Barri Evins talks “toppings” in the fourth and absolutely final article in her mouthwatering series on how to write a screenplay based on making a pizza! Learn how to choose the extra ingredients from flashbacks to big reveals, plus narration, montage, and metaphor to enhance your story but not overwhelm it. With examples from top films plus a Writer’s Workout exercise.

My idea that making a pizza from scratch was a tasty metaphor for the steps in how to write a screenplay mushroomed (hahaha) from a slice to and XXL of articles.

In Part One, we discussed starting with the crust. Focusing on the foundation first – the big decisions that will shape and support your story.

In Part Two, we explored into the idea of theme as the richly flavored, long simmered sauce that makes story delicious. And we got a taste of A-List writers and the themes that draw them to stories time and again.

In Part Three, I delved into the idea that cheese is like structure, melting and melding everything together and hold the events in place.

At last, it’s time for “toppings!” These are the “extra” elements that can enhance your story or… overwhelm it.

Hope you still have an appetite!

Choosing Your Toppings

I’m dubbing what many would call “devices,” Toppings. There are plenty of enticing options on the menu, but these added ingredients are optional and should be selected with care:

- Supporting Characters

- Flashbacks

- Narration

- Montage

- Metaphor

- Reveals

Choose only what enhances and elevates your story; never inundate it an effort to make it seem tempting. Heaping them on in hopes of adding interest may add razzle-dazzle will not sell us on your story. In fact, they might obscure or even smother the solid story underneath.

Supporting Characters

In my opinion, crafting strong Primary Supporting Characters who fulfill an important function in the story is not optional but essential.

The villain, the love interest, the confidant, the sidekick are all significant people in the life of your protagonist that impact the story should also fill a specific function. In elevated writing, nothing is random.

I often use the metaphor of a wagon wheel to illustrate the role of Primary Supporting Characters. (Can I even use a metaphor within a metaphor?) The hub is the central idea of the story – its theme. Primary Supporting Characters can offer a different point of view, contrasting with the hero’s. This can bring added depth to the message and make the story roll forward effectively.

Jaws is a great example because of the clear and dynamic role of the Primary Supporting Characters. This horror story is about fear. Protagonist, Chief Brody, has a crippling fear of the water. The hub of this wheel is “fear of the water.” Brody is one spoke. Fearless oceanographer, Hooper, studies and loves sharks, representing another spoke. Quint, is a seasoned seaman and zealous shark hunter, provides a third spoke in the wheel. These characters exemplify sharply opposing points of view on the theme. This pushes and prods Brody throughout the story. Read more Jaws analysis here and find a related Writer’s Workout from my Screenwriting Elevated seminar.

But a main character’s world must be fully populated. Even the small roles count. Overlook them and you’re throwing away an opportunity to add flavor to your script and texture to your story.

After reading the book Bulletproof: Writing Scripts That Don’t Get Shot Down by the very talented writing team, David Diamond and David Weissman, and being a longstanding fangirl of their work, (The Family Man, Evolution) I was eager to read their advice to screenwriters.

The book is chock-full of “nuggets of wisdom,” but when I got them in a room for an interview, they kept offering up very quotable advice, including how and why smaller roles matter:

"Take the smallest roles in your movie and try to enhance them. It is helpful beyond measure. It impacts the experience of reading the script. Imagine you’re an agent or a producer or a studio executive and you’ve got a stack of ten scripts to read over the weekend. You pick up this one and you open it up, and on page four there’s a causal encounter between the protagonist in the movie and someone that might not be in the movie ever again. And that little character has a voice and a point of view and a sense of humor. You feel like, “Oh what a delightful script this is. I’m not going to toss this aside and go to the next one. I’m just going to keep going because who knows what I might find. There’s a surprise every 10 pages. I meet someone new and they’re not just saying, ‘Can I get you a cup of coffee?’” And they’re going to keep reading. Give them a flavor, give them a point – it’s like spices when you’re cooking."

David Diamond

I swear, I did not encourage that cooking metaphor! It happened completely on it’s own, long before I’d even dreamed up my pizza analogy.

But it’s great advice. Look at those small roles, often portrayed as generic, and make them into gems. Explore how they add dimension and have a point of view on the theme to add flavor and impact to your screenplay and strengthen your storytelling.

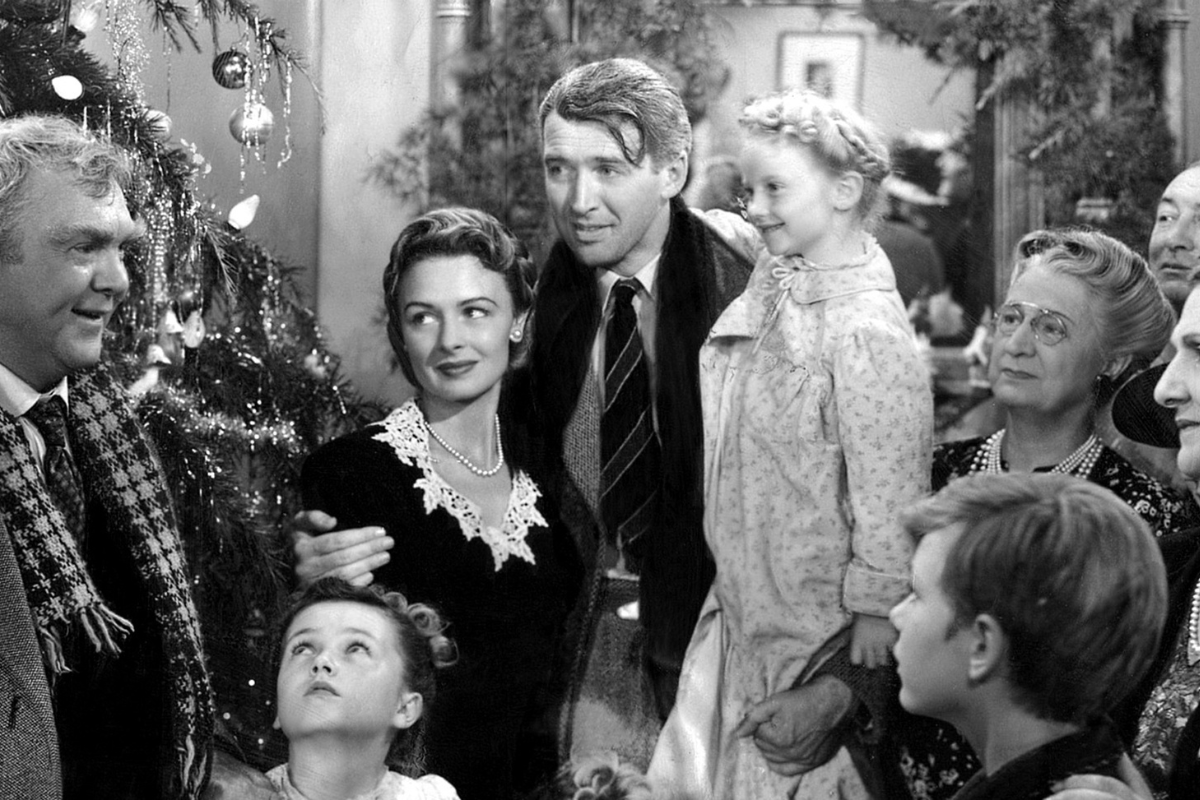

It is a hallmark of The Davids, as they are affectionately known, and it makes their writing delicious. Throughout The Family Man, a delightful spin on It’s a Wonderful Life, not a single role is wasted.

Protagonist Jack, a rich, ambitious, playboy portrayed by Nicolas Cage, could easily be unlikeable – and more significantly – unrootable in lesser hands. As we are introduced to him, cleverly crafted quick interactions with small characters reveal added dimensions to Jack, showing that he treats others with humor, respect, and generosity, and notably, without regard to their social ranking.

From the snobby “old money” older woman Jack rides with in the elevator, to his doorman, the valet, and his assistant, each encounter is a little gem that takes a potentially unrootable protagonist and humanizes him.

Flashbacks

To flashback or not to flashback, that is the question. Whether ‘tis essential or not is the answer. Sparingly is always best. Where you place it is the added dilemma.

Leaning on the flashback to convey backstory is a shortcut versus finding a way to reveal exposition in action.

The well-placed flashback might be held off, and ultimately revealed as the missing piece at just the right moment.

Was there ever a more lovely flashback than in Casablanca? Why is the Rick we meet so cynical, so selfish, interested only in money? In a world at war, Rick says, “The only cause I care about is myself.” What happened in Paris?

Thirty-nine minutes into a film that runs an hour and 42 minutes there is a delicate transition to a lengthy flashback that tells the entire backstory of Rick and Ilsa. The script by Julius J. Epstein & Philip G. Epstein and Howard Koch deliberately sets the stage for a lengthy flashback, a complete story within a story.

Sam enters, and Rick says, “Of all the gin joins in all the towns in the world, she walks into mine.” Drunk, he insists, “You played if for her and you can play it for me.”

MONTAGE - PARIS IN THE SPRING STOCK SHOTS

Moving into:

Rick is driving a small, open car slowly along the boulevard. Close beside him, with her arm linked in his, sits Ilsa.

Moving into scenes showing them in love, progressing to scenes with dialogue.

A captivating flashback sequence lasts nearly ten minutes, but is essential to revealing backstory – that they loved each other, and that she broke his heart.

Only much later, one hour and twenty minutes in, is the final piece of the puzzle revealed, over a bottle of champagne, a call back to the earlier scene. Ilsa explains what happened on the day they were supposed to run away together. She confesses she still loves him and would never have the strength to leave him again, not even to be with Laszlo. Ilsa says, “You’ll have to think for both of us, for all of us.” He replies, “All right, I will.” And then that line, in a film full of iconic lines, is repeated, “Here’s looking at you kid,” affirming that he is still in love with her.

While this flashback is backstory, it happens in the context of a dramatic sequence that begins at gunpoint, echoes the earlier flashback, and sows the seeds to advance the story to its inevitable surprise ending.

Narration

Narration can be a crutch to externalize a character’s inner thoughts and feelings or great tool when used deftly. While we see narration often in films that are adaptations of novels or short stories, mediums that allow the writer to readily delve into the mind of characters, it can be a topping that brings an extra flavor to your story – if and only if it enhances the material.

Beyond telling, narration should bring added meaning that could not be achieved any other way. For instance, some narrators tell us a story about their childhood, reflecting back at adolescence from the perspective of adulthood, such as in Stand by Me, by Bruce A. Evans and Raynold Gideon, adapted from a Stephen King novella, The Body.

Plotting the use of narration is essential. Sometimes scripts lean on narration in the set up, to do some of the heavy lifting of exposition and character introduction, only to drop out abruptly and jump back in later, jarringly. Charting its use over the story can help you focus on when it is really necessary, as well as make for a smooth transition by tapering off, especially if it is going to appear again in the story.

In Big Fish, written by John August, based on the novel by Daniel Wallace, Big Fish: A Novel of Epic Proportions, narration is used in two ways to added meaning.

The primary narrator is Edward, played by Albert Finney, the teller of tales, imbuing the story with his distinctive, larger than life perspective on the world. It matches his raconteur character while advancing the through line.

But there is an additional narrator here. His son, Will, the protagonist, played by Billy Crudup, speaks to us in voice over twice, once at the beginning, and once in the end.

In the first pages, Will’s narration conveys the protagonist’s perspective at the outset. It underscores the father/son conflict at the heart of the story and foreshadows both how Will is changed by the story, as well as hints at the climax of the narrative. In a single page, a lean minute of screen time, August skillfully interweaves voice over with engaging visuals that accomplish many things simultaneously. They add a significant facet to Edward’s character that pays off later. They create a smooth transition to a flashback that beautifully establishes young Edward, and includes a moment of surprise in the narrative. Accomplishing this many tasks in a highly cinematic sequence sets a high water mark for narration.

On the final page, set years after his father’s death, Will’s narration appears again, illustrating his arc. Now that Will has become a father himself, August implies in action, rather than showing which would feel predictable and be heavy handed, that he too has become a storyteller. Will has overcome his fear of becoming like his father and embraced his legacy – closure to his arc. The narration underscores the deep and resonant theme.

Big Fish is a love story to story itself. It tells the larger than life story of a man’s life through his many colorful stories, and is about the power and the magic of story that enables us to live on after death.

After seeing Big Fish in the theatre, I wept in the parking lot for an hour. When I read the script before assigning it to my students, damn if John August didn’t make me cry again, with words alone.

When it comes to the decision of adding narration as a topping, these are the other big questions to ask:

- Does it fit with and support the tone of the story?

- Is it a good match for the character?

- What does it add to the story which is significant that we could not know otherwise?

- How does it support the larger meaning of the story?

- Can it work in tandem with other elements to accomplish multiple tasks at once?

Montage

To be honest, montage would not be one of my favorite storytelling devices. Why? Predictability and laziness.

Montages primarily serve one of two purposes – to show progression of time or the development of a relationship. That familiarity instantly gives them a generic feel that you must figure out how to overcome.

The first is used to condense a series of sequential events. It may be essential to show time is passing, and we are well past the era of shooting a clock with fast spinning hands. Push yourself to explore other options.

The latter is most easily defined by the “falling in love” trope. We see the couple take hold hands, walk on the beach at sunset, go on a picnic, cavort like kids, and melt into a deep kiss. Predictable and cliché, yet effective. Can you find an innovative alternative, a fresh spin that is unique to your story and characters? (500) Days of Summer used a nonlinear structure to explore the development and dissolution of a relationship.

Outstanding montages are lean, deft, and cinematic. Think Hugh Grant in Notting Hill written by Richard Curtis, as William deeply misses Anna over time, walking through the seasons in a seemingly single take and location, set to the perfect song to externalize Will’s inner thoughts and feelings.

Wondering if that was in the script or created on the set? Here is Curtis’ second draft:

Not too much, not too little. Deftly done to convey the writer’s intention. Without calling every shot, it brought the writer’s vision to the screen in a way that is vibrant and resonant.

There is a later script version that adds more detail, highlighting the pregnant woman in the beginning seen later with her baby, but is still only just more than half a page. Note that a specific song is not specified by the writer, only the tone he is aiming for, which became the poignant “Ain’t No Sunshine,” written and performed by Bill Withers, perfectly underscoring the hero’s emotions. Watch here.

Beautiful, but now that it’s been done, you can’t do it. Come up with something original that is unique to your story, your characters, and fits the tone and message of your story.

Metaphor

I do love a great metaphor, and believe, when skillfully employed, it is a sign of elevated writing. I am not talking about a figure of speech, such as “That script is a diamond in the rough,” but rather the concept of that stems from the etymology of the word. Ironically, the word “metaphor” is actually a metaphor, derived from a Greek term meaning to “transfer” or “carry across.” According to Wikipedia, “Metaphors “carry meaning from one word, image, idea, or situation to another, linking them and creating a metaphor.”

Film is an ideal medium for visual metaphors that represent a concept. They symbolize something larger, such as the character’s flaw or the theme, or reveal inner thoughts and feelings. It is a nuance that might not strike you immediately, but on further reflection. It might be open to interpretation, evoking a different response or connotation based on our own beliefs and perceptions. Which is precisely what makes them powerful.

Rather than spelling something out, metaphor draws the reader and the audience into the storytelling by allowing and encouraging them to assign meaning and evoking an emotional response in us.

Highly effective metaphors are choreographed to run throughout a script. I like The Rule of Threes, not too much, but not too little. Just like a solid joke, there is a set up, a pay off, and a call back. And just as a screenplay has three acts. The use of the metaphor should be spread over the course of the story.

The Shawshank Redemption, written and directed by Frank Darabont, based on a novella by Stephen King, is rich in metaphor. The prison itself, with a setting so profound that it is nearly a character itself, is a metaphor. The overarching metaphor goes directly to the theme – the abstract construct that “hope can set you free.”

With hope, Andy, portrayed by Tim Robbins, is never truly imprisoned; without hope, Morgan Freeman as Red will never be able to be free, not even when he is paroled.

Metaphor excels at conveying the abstract with a concrete element.

While the prison represents hopelessness, music represents freedom. From Andy playing opera over the PA system, to his gift of a harmonica to Red, who is unwilling to play it, music symbolizes freedom.

We hear the aria play over a series of shots that show its impact on everyone in the prison. We hear Red’s narration underscoring the metaphor:

Andy is thrown in solitary for this stunt, but when he gets out proclaims it was the easiest time he ever did, because he had the music with him. This is an abstract concept that Red does not grasp, but needs to learn to succeed on his journey to hope and freedom.

James Whitmore as Brooks serves the role that I reference as "The Ghost of Christmas Future." Brooks has been in Shawshank so long he has been “institutionalized.” Once free, he cannot survive outside. This is where Red is headed if he does not change over the course of the story. Hope is life; institutionalization is death. Thus the iconic and resonant line, “Get busy living or get busy dying.”

Reveals

I love, love, love a really good reveal. If someone is describing a surprise element in a movie or series I haven’t yet seen, I will plug my ears and neener-neener loudly. No spoilers – I crave the experience!

That delightful sensation when the dominoes tumble or the other shoe drops and we – both the audience and the character – put the pieces together. This is more than entertaining, it is a full on rush of feel good chemicals flooding your brain. I will not be deprived of that.

As I’ve written before, all stories – no matter the genre – need tension and suspense to keep us engaged. Your reveal may not be as big as the meaning of, “I see dead people,” or the true identity or Keyser Söze, but think carefully about when and where you give your audience key added information.

What needs to be established to grasp the story at the outset, and what will pay off richly if saved for later?

Let It Bake

Even after you’ve gone through all these steps to make a delicious pizza, there is an essential task remaining before it is ready to serve. It needs to bake. And that takes time.

Just as with creating a story, makes all the hard work and many steps that have gone before, pay off. This is where every single element comes together. The result is greater than the sum of its parts.

Naturally, it’s exciting to type, “Fade Out,” and be done, but if you have been working at it this long and hard from the very start, do not rush now. It is a time to pause. To rest. And then undertake the final step – another pass.

Even if you truly believe that you are done, stop. Step aside. Wait. Distance allows you to return with some perspective.

You must serve us a fully baked story – in all its crispy, savory, melted, distinctively tasty deliciousness.

Don’t rush to get it out into the world. You may be aiming for a contest deadline, or a self-imposed one. You might be eager to query. But when it comes to the industry, you really only get one chance. That first impression is everything.

There's a whole lotta’ pizza out there. “Good enough” is not good enough. Make yours so delicious we ask for more!

Read more on how, when, and why to “slow your roll” and elevate your writing process here.

Before you serve it up, let it bake!

The Topping Taste Test

The key is to find favors that work together. For every topping, ask these questions?

- Does it serve a function?

- Does it advance the story?

- Does it reveal character?

- Does it support the tone?

- Does it accomplish more than one purpose?

- If it was cut, would we miss it?

It all comes down to this question: Is it necessary?

If a device plays a role in the story that could be fulfilled in any other way… it does not belong.

While the pizza analogy is all mine, I won’t claim credit for the deliciousness of simplicity.

Aristotle, considered one of the most influential people who ever lived, contributed to almost every field of human knowledge then in existence, and was the founder of many new fields. More than 2300 years after his death his words continue to resonate. It is no surprise that he had a few words to say about “too much” that have been echoed throughout the centuries:

An element whose addition or subtraction makes no perceptible extra difference is not really a part of the whole.

The Poetics, Aristotle

I think that would be the noted thinker and philosopher’s way of saying, “Don’t put too many ingredients on your pizza,” – if pizza existed in 380 BCE. On the other hand, Aristotle might possibly have had pizza, since foods similar to pizza have been made since antiquity. Topping bread with ingredients to make it more flavorful can be found throughout history.

But they didn’t call it “pizza” until the Italians cooked it up 997 AD.

May your story be molto delizioso!

And just in case you’re contemplating sending a pizza my way…

Thin crust, extra sauce, more than one type of cheese, topped with tomato, onion, and bacon.

Learn more about the craft and business of screenwriting from our Script University courses!

Barri Evins draws on decades of industry experience to give writers practical advice on elevating their craft and advancing their career. Her next SCREENWRITING ELEVATED online seminar with 7 monthly sessions plus mentorship will be announced in 2025. Breaking & Entering is peppered with real life anecdotes – good, bad, and hilarious – as stories are the greatest teacher. A working film producer and longtime industry executive, culminating in President of Production for Debra Hill, Barri developed, packaged, and sold projects to Warners, Universal, Disney, Nickelodeon, New Line, and HBO. Known for her keen eye for up and coming talent and spotting engaging ideas that became successful stories, Barri also worked extensively with A-List writers and directors. As a writer, she co-wrote a treatment sold in a preemptive six-figure deal to Warners, and a Fox Family project. As a teacher and consultant, Barri enables writers to achieve their vision for their stories and succeed in getting industry attention through innovative seminars, interactive consultations, and empowering mentorship. Follow her on Facebook or join her newsletter. Explore her Big Ideas website, to find out about consultations and seminars. And check out her blog, which includes the wit and wisdom of her pal, Dr. Paige Turner. See Barri in action on YouTube. Instagram: @bigbigideas X: @bigbigideas