Behind the Lines with DR: The Tamale Principle

The Tamale Principle… A simple axiom. When faced with a choice between the unfamiliar and the familiar, most people will choose the latter. At least, thus was the theory posited…

The Tamale Principle... A simple axiom. When faced with a choice between the unfamiliar and the familiar, most people will choose the latter. At least, thus was the theory posited by my old man when describing one of the quandaries of a democracy.

Hang with me here if you want to know how this relates to showbiz.

Now, if I recall correctly, my father-the-politician used this theorem to explain to his ten year-old-son—namely me—why the better man (in his opinion) had lost a particular election.

“Well, it’s kinda like when somebody goes to a Mexican restaurant for the first time,” he told me.

Now, mind you, this was well before Taco Bell was a sea-to-shining-sea brand and breakfast burritos were served in every public school.

“Imagine this person is reading the menu,” he continued. “And they barely recognize a single item. But they have heard of a tamale. Maybe even they’ve had a tamale before. Chances are, when the waiter comes to take their order, they’re gonna order what?”

“The enchilada?” I messed.

“They’re gonna order the tamale,” my dad finished, deadly serious. “At least most people in that spot are going to order what they know over what they don’t know.”

Thus ended the lesson. Funny how I’ve never forgotten it, either. Though, not until recently had I ever really applied it to my beloved movie business.

A few weeks ago, while out of town with my son, we had an idea about going to a movie. With a handy app on my phone, we checked out what was playing at the local multiplexes. I’m sure you see where this is going. Not only were the same flicks playing at all the nearby movie houses, but nearly each and every one had an overly familiar feel. But for one Oscar leftover, our choices were a pair of sequels, a remake, a re-launch of a franchise, a Marvel movie, a picture promising loads of CGI-generated action scenes, and a stand-alone picture whose ad campaign pandered to the target audience of a recent Christmas tentpole.

“Oy,” I said aloud in the Yiddish parlance of my show-folk brethren.

Even my son couldn’t find the mojo to want to plunk down his father’s Amex card in order to view one of those dogs queued up at the cinema.

Now, a quick disclaimer: One or more of those pictures could’ve been quite a dandy despite the ho-hum exterior. Or even more relevant, they might’ve been one of mine. And in either case, I’d have been annoyed as hell that somebody who loved movies would’ve been left yawning at the gate instead of buying some popcorn and buckling up for a two-hour movie ride.

My point is this: We are no longer dining in an unfamiliar restaurant, faced with a menu full of exotic and exciting fair. The menu being offered to the motion picture consumer is ninety percent familiar. It’s as if everything on the marquis is now a tamale. The big studios are no longer selling us what we want. But even worse, what we expect.

How did we get here?

Forgive my gray hairs, but the business used to rely a lot more on imagination and less on reconstituted, microwavable fare.

Say, for example… A writer wrote a script that garnered strong interest from a producer or studio or star or director. Not because it fit a particular stratagem or target demo, but because it was damn good, moved them from either tears or laughs or dreams of box-office gold. The project was then presented to a savvy studio head—the kind that loves movies the same way he or she did as a kid—who insisted that the movie needed to be made. The wise studio boss gathered his production minions, came up with a dollar figure the studio felt was worth risking on the picture, and off the filmmakers went with a simple warning: work hard, make a great picture, and stay the hell on budget.

Now, depending on the studio and personalities involved, maybe the marketing folks were given a heads up on the pictures currently in production. But mostly, the marketing squads had their hands full with the nearly completed films that were in post-production. Most of their efforts were focused on what was in front of them rather than what was currently lensing.

Once the movie was delivered, be it a big budget star vehicle or some smaller, riskier venture (think seminal films like Midnight Cowboy or Taxi Driver), the studio jefes would weigh in on whether the movie lived up to their expectations and then—and only then—would the marketing guys begin their voodoo, a magic that could land anywhere between Hey, I know how to sell this? to I love it but what how do we serve this to middle America?

It wasn’t easy. But it did get done. Movies landed in theaters on their appointed release dates. And audiences were consistently treated to a marquee menu of differing tastes and textures, from the familiar to the sublime.

That was then.

Somewhere along the way, the word “blockbuster” went from being the descriptor of a movie that went beyond profitable and something that surpassed the normal business expectation to the nascent objective of nearly every Hollywood executive with plans for advancement. If a studio picture failed to breach the magic hundred million dollar ceiling in domestic box office, that movie was considered a failure. To insure as much, those genius marketing mavens who were often housed outside of the studio’s main administration building, found themselves moving closer to the executive suites and being invited into internal development meetings. The mantra of making the movie because we love it morphed into making the movie because we know how to market it.

In other words, if they don’t know how to market it before they green light it… they simply don’t. To which I reply that major studios are no longer in the movie business as much as they have allowed themselves to become a risk-averse, surprise-free, tamale-making enterprise.

Of course, there’s the indie route. It continues to shift and shine, finding financing wherever there’s a tax break or a new crowd-funding site. And God Bless the new visionaries who’re building the next exhibition platforms that, I hope, will continue to draw dollars and eyeballs away from the old tried and true—which I’m afraid has evolved into the tried and tried and tried again.

I can’t rightly say what the future holds. Nor can anybody for that matter. All I know for certain is that people young and old will continue to have an appetite for entertainment. It’s what we put on the menu that will either keep them coming back for more or drive them away in search of a more varied and nutritious fare.

- Read more articles by Doug Richardson

- Nicole Perlman Q&A: How ‘Guardians of the Galaxy’ Went From a Writers Program Project to Record-Breaking Film

- Legally Speaking, It Depends - Producers

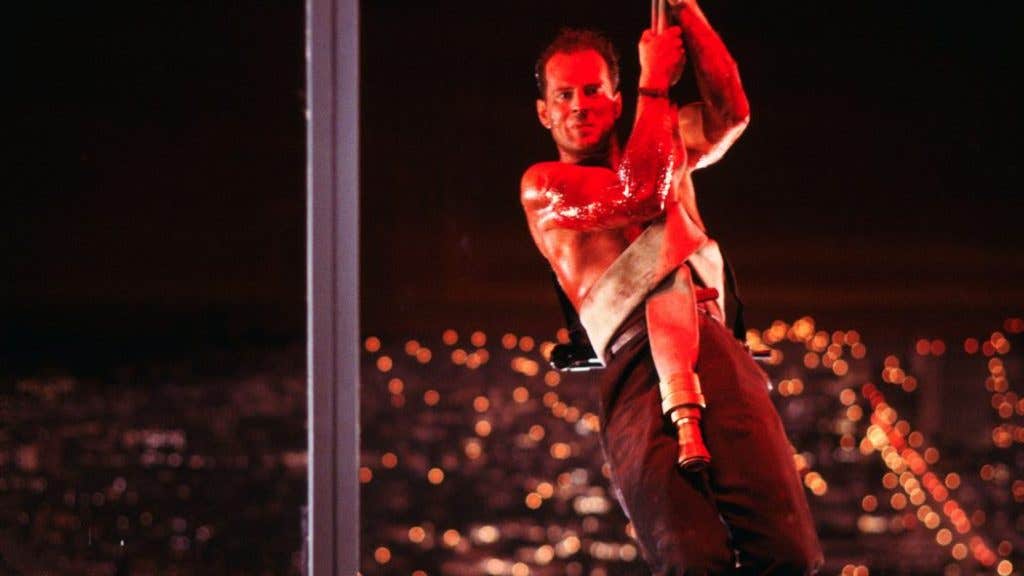

Doug Richardson cut his teeth writing movies like Die Hard, Die Harder, Bad Boys and Hostage. But scratch the surface and discover he thinks there’s a killer inside all of us. His Lucky Dey books exist between the gutter and the glitter of a morally suspect landscape he calls Luckyland—aka Los Angeles—the city of Doug’s birth and where he lives with his wife, two children, three big mutts, and the dead body he’s still semi-convinced is buried in his San Fernando Valley back yard. Follow Doug on Twitter @byDougRich.