Script Gods Must Die: The Screenwriter as Playwright – David Mamet

Click to tweet this article to your friends and followers From Merriam-Webster: icon noun \??-?kän\ computers : a small picture on a computer screen that represents a program or function…

From Merriam-Webster:

icon

noun \??-?kän\

computers : a small picture on a computer screen that represents a program or function

: a person who is very successful and admired

: a widely known symbol

Gotta be lonely, being an icon. Genius is defined by its very absence in every day life. You know you’re in the presence of genius because of its rarity. You know it when you see it.

Quite some time ago I had a chance to work with J.J. Johnston and Jack Wallace. These are Mamet guys. If you want to know that means all you need know is that the play American Buffalo is dedicated to “Mr. J.J. Johnston of Chicago, Illinois.” J.J. is the classic Third Guy On The Left in bigger budget flicks like Fatal Attraction and JFK. Mamet gave him roles in State And Main and The Spanish Prisoner. One tidbit you might miss in his IMDB profile, hidden away under Trivia is that he was nominated for a 1976 Joseph Jefferson Award for Actor in a Principal Role for "American Buffalo" at the St. Nicholas Theater Company in Chicago, Illinois. J.J. was Donny Dubrow in the original production of American Buffalo. Jack Wallace you’d know from The Bear. Where you wouldn’t know Jack from would be his five Jefferson Award nominations or that he was another of David Mamet’s original Chicago guys.

The remarkable thing as a playwright working with these old geezers was that just by listening to them…I could hear Mamet…right from their mouths! After a very short time I found myself starting to recognize the gems they were spewing, and sought a pen. Remember, playwrights—if words are in the air and you lay them down—you just wrote it. For you Wisenheimers, yeah, that means conversation.

I was filled with admiration for Mamet when I realized that he had done likewise. Surround yourself with a Chicago crew, kick back and record their pearls—hearing it, the authenticity of the dialogue, and laying it down in a totally original way. That is Mamet’s genius. Because this wasn’t mere dictation he was doing. It was fitting reality into his creation. Using everything real life brings for your art. A life lesson indeed.

Interesting to compare Mamet’s plays with their movie adaptations. I’ll probably miss a couple, but the plays he’s written and filmed are several(in chronological order): A Life In The Theater (twice-1979/1993), About Last Night (twice-1986/2014), The Water Engine (1992), Glengarry Glen Ross (1992), Vanya On 42nd Street(1994), Oleanna (1994), American Buffalo (1996), Lakeboat (2000), Edmond (2005).

Should we just take the suspense out of it and say that other freakin’ Shakespeare, this is the most prolific stage-to-film playwright in history?

The Mamet stories I heard coming out of Chicago were legendary. One story recounted in Richard Christenson’s loving portrait of Chicago Theater, A Theater Of Our Own, has Mamet walking into The Goodman Theater and handing off American Buffalo to Gregory Mosher, “promising in a bit of vainglory that he would put five-thousand dollars in escrow as a guarantee that the play would win the Pulitzer Prize.” And while it wasn’t until Glengarry Glen Ross in 1984 that Mamet earned his Pulitzer, American Buffalo opened on Broadway in February of 1976 to a Frank Rich review calling it “one of the best American plays of the last decade.”

So, why did it make for a mediocre movie—especially when it had young Dustin Hoffman playing the lead role? Roger Ebert, in his review, put his finger on the cause: “It is a cliche, but true, that some plays have their real life on the stage. “American Buffalo” is a play like that--or, at least, it is not a play that finds its life in this movie…On the stage, they are trapped in their space and time. In this film (although the action has been opened up only minimally), they seem less confined.”

That’s it, exactly. On the stage they are trapped in space and time. When you open things up—which you inevitably do for a film—you lose that. This is the Bermuda Triangle for playwrights: How do you take the verbal nature of theater and transmute pure language to the language of imagery that is required for a film? A movie theater audience is an entirely different animal. They aren’t paying to see a play on film. The play must be re-imagined for the new medium.

Glengarry Glen Ross faced the same difficulties, but with more success. Full disclosure: If a .9mm Beretta were put to my head, yes, I could recite the Alec Baldwin “Put…that…coffee…down!” monologue from memory. What you might not know is that that monologue isn’t in the original play. You can find it here. And here.

It was written for the film, for Alec Baldwin specifically, and isn’t the only change going from play to film.

Borrowing from the elves at Wikipedia:“Once the film's cast was assembled, they spent three weeks in rehearsals…Harris remembers, "There were five and six-page scenes we would shoot all at once. It was more like doing a play at times [when] you'd get the continuity going”, Alan Arkin said of the script, "What made it [challenging] was the language and the rhythms, which are enormously difficult to absorb".During filming, members of the cast who were not required to be on the set certain days would show up anyway to watch the other actors' performances.”

In the play you’ve got four scenes: 1-Chinese restaurant 2-Chinese restaurant (later) 3-Restaurant (later) 4-Real estate office. Total of two locations. Now think about the movie. Sure, we keep the Chinese restaurant. The real-estate office, too. But we’ve also got scenes with Jack Lemmon in a driving rainstorm at a telephone booth. We got Lemmon and Spacey on the street in the same rain, Lemmon trying to bribe him. There’s a full scene inside a customer’s home, Lemmon trying to sell the customer. It’s a movie, we have to see that! Then we’ve got full scenes at the bar with Arkin learning of the theft plans of Ed Harris, being drawn in to the conspiracy.

Writing movies, as Robert McKee informed, is about making choices of inclusion and exclusion. Could we use a scene of the Alec Baldwin character talking to “Mitch and Murray”? Sure…but to what gain? By expanding out too far you dilute down the play for visuals sake alone and force the movie either to go longer or make cuts in the existing dialogue. Figure out what you need to see, then write that. W don’t need to see a meeting with Mitch and Murray. We don’t need to see Baldwin at all before the monologue, or after.

The choice of not showing the robbery was ballsy. You intensify the mystery of who robbed the place by not showing it.

The movie was no blockbuster. It didn’t even make its money back. I love that Mamet made a million on it though. Again, from the Wikipedia elves: “Mamet wanted $500,000 for the film rights and another $500,000 to write the screenplay. (Stanley R.) Zupnik agreed to pay Mamet’s $1 million asking price.”

Put me on a desert island with American Hustle, Wolf Of Wall Street, 12 Years A Slave, Dallas Buyer’s Club and Glengarry Glen Ross…

Take a guess which movie this Chicago playwright is reaching for.

- More Script Gods Must Die articles by Paul Peditto

- Notes from the Margins: Every Article on Screenwriting You Never Have to Read Again

- Script Angel: Turning Screenwriting Dreams Into Achievable Writing Career Goals

Get advice in David Mamet's book,

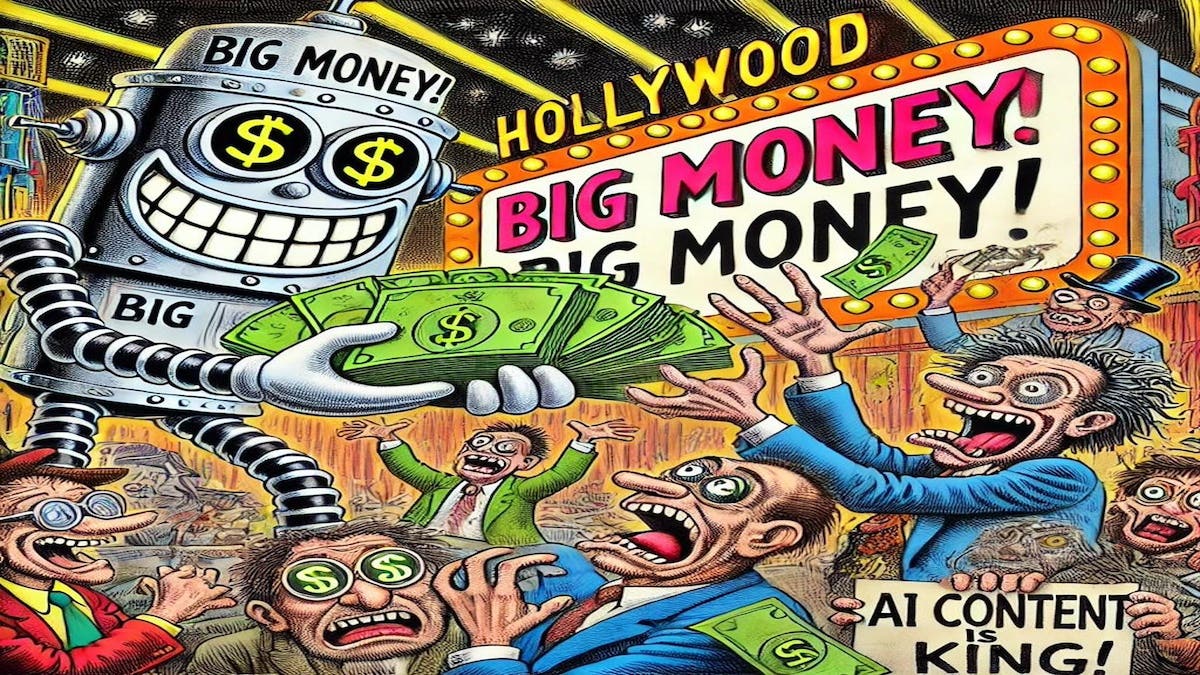

Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose and Practice of the Movie Business

PAUL PEDITTO is an award-winning screenwriter and director. His low-budget film Jane Doe starring Calista Flockhart won Best Feature at the New York Independent Film & Video Festival. He just finished production (Nov. ’24) on Dirty Little Secrets, a $350,000 dollar Indie feature shot in Chicago. Six of his screenplays have been optioned including Crossroaders to Haft Entertainment (Emma, Dead Poets Society). He recently wrote and produced the micro-budget feature Chat, currently distributed on TUBI, iTunes, YouTube, and Dish Network by Gravitas Ventures.

Over the past decade, Mr. Peditto has consulted with over 1,000 screenwriting students around the world. He has been a Featured Speaker at Chicago Screenwriters Network, Meetup.com, Second City, and Chicago Filmmakers. He has appeared on National Public Radio and WGN radio, and reviewed in the Chicago Tribune, Chicago Sun-Times, L.A. Times, and the New York Times.

Peditto is an adjunct professor of screenwriting at Columbia College. Under his guidance his students have written and produced films that have appeared in major film festivals, have semi-final placings at Nicholl Fellowship, and have won awards and screened at film festivals around the country. His new book, The DIY Filmmaker: Life Lessons for Surviving Outside Hollywood is available through Self-Counsel Press on Amazon. Follow Paul at www.scriptgodsmustdie.com and on Twitter @scriptgods.