A Screenplay to Remember: Ira Sachs and Maurico Zachiaria’s ‘Love is Strange’

‘Love is Strange’ by director Ira Sachs and Mauricio Zacharias touches on questions that have always been important to older Americans.

Bob Verini is the Los Angeles-based theater critic for Daily Variety, for whom he also contributes features on film, theater and television. Since 2000 he has been a senior writer for Script.

Not since Leo McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow, or Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, has a fiction film so poignantly touched on the plight of the elderly in modern society as Love Is Strange, which debuted in early fall to great acclaim and has remained part of the awards conversation all season long.

It’s easy to understand why. The sensitive screenplay by director Ira Sachs and Mauricio Zacharias touches on questions that have always been important to older Americans, and which will become even more pressing in the very near future: What happens when health advances allow more and more of us to outlive our money? Who will step forward as caregivers, when families are already stretched thin? What’s the effect on family life when an elderly relative comes to stay? And how will same-sex married couples in particular, who may enjoy less blood-relative support, cope with the so-called golden years? Longtime companions Ben (John Lithgow) and George (Alfred Molina) are no sooner married – thanks to the up-to-the-minute changes in New York State’s laws – than they’re forced by cash and circumstance to part, and if that doesn’t move you, you’d better check for a pulse.

The Sony Pictures Classics release has received four Independent Spirit Award nominations, including one for its screenplay, leading to increased speculation that the writing at least could be cited by the Motion Picture Academy when Oscar nominations are announced on January 15, two days after the picture is released on DVD. In late August, Script sat down with Sachs to discuss the writing process that resulted in this delicate, fascinating story.

The Memphis native began by reviewing his early experiences directing theater at university, after which he transitioned into filmmaking with such distinctive personal projects as The Delta (1996), Forty Shades of Blue (2005), and the 2012 film festival favorite Keep the Lights On. Those films, especially the first two, have a loose, semi-improvisational feel (he cites Cassavetes as an early influence). But over time, he asserts, “I’m more and more interested in constructing a narrative from a more conscious place. Now my films are less digressive than they used to be. There’s a dramaturgical unity that’s more classic, in a way.”

Script: Do you write treatments, or biographies for your characters? That would be a fairly classic approach.

Sachs: Well, I have a wonderful collaborator, Mauricio Zacharias… he and I have a really good process of how we work as a team, and we’re deep into our third film now. We spend six to eight weeks talking about movies in terms of story and character and world. We hone those conversations down to a pretty conventional logline, That’s really something that I'm attached to. I think of it as, you need to know the coat hanger, and then you can hang a lot of coats on it. You can move away from things if you actually know where you’re going. But where you’re going is the suspense of storytelling that I think is very crucial to being a filmmaker. I'm interested in artistic rigor, and in demanding that I succeed on the level of my heroes. Henry James. Bresson. I’m working in the genre of narrative cinema.

Now, I don’t want to diss avant garde, because the avant garde has been very important to me. And actually it asks different questions, in the presentation and in the economy. The experimentation, and the risk of subjects, of the avant garde have influenced me. I’ve been very influenced by the artists of New York of the 70s and 80s who were radical. And particularly with the homogeneity of today’s American cinema, I find I need to tap into those voices.

So, Mauricio and I talk for a time, and he actually writes the first draft of the film.

Script: And when you’re together, is one of you the “typer,” and the other the “pacer,” as Billy Wilder used to say?

Sachs: No, because we hardly ever, until the very last draft, work in the same room after the initial conversational period. I think I’m skilled at being a collaborator, and one of things I’ve learned is that it’s important to give your collaborator space for flights of fancy that are separate from you. And everything does not need to be articulated; everything doesn’t need to be spoken.

Script: That’s interesting. I guess sometimes if you’re together in the room, a good idea can get quashed too quickly.

Sachs: I find the same thing when I work with actors. I don’t rehearse my actors before we start shooting. We talk, but two words I think should be forbidden on set are “subtext” and “motivation.” They’re words I don’t want to hear anything about. Because to define them is to limit them.

So I try to create a situation in which I remove myself, while being very attentive. And in that way it’s very much like psychoanalysis, where you want the person on the couch to have room to fly, and yet they’re – oh – in company. “Company,” I think, is a really great word. Beckett wrote a play called Company. It defines a lot of what my job is about.

Script: Do you know, early on, how a screenplay is going to wind up?

Sachs: Oh, definitely. I feel like I have to know where the film is going to end. It can change, in editing, but in Love Is Strange we knew it was a film about the cycles of life. We knew it was a film about generations. And so the final act was a return, in a certain way, and a handing off which occurs. I really knew where that film was going.

I felt the production of this film was what I can fantasize about what being on a studio film was in the 30s. We wrote a script that worked; we cast great actors; we cut it in about 10 weeks; we premiered it at Sundance; and it was all very fluid. And I liked that.

Script: It felt a little bit like Kramer vs. Kramer to me, one of my favorite Hollywood visits to domestic life. Like that film, it felt clean in the best sense, of people trying to keep their life tidy. It seemed well-thought-out but not over-calculated. And also like Scenes From a Marriage, it felt linear yet you were dropping in and out on the characters at unusual and striking moments.

Sachs: That’s really a nice allusion. No one’s mentioned that before.

I feel it’s a film I couldn’t have made at any other point in my life, for a number of reasons including the filmmaking and storytelling skills that I’ve worked on. But also, the optimism of the film is something I couldn’t have had five years ago, and for that reason, it feels very timely, but for different reasons than might seem apparent.

On the surface its timeliness has to do with the laws of marriage equality, but to me that’s just the engine of the story. What’s really timely, to me, is that the culture has changed who I am: as an individual; as a gay man; as a married man; as a father. Those very real changes have made it more possible for me to believe that love can last. Because I think the world embraces my love in a different way. That’s somewhat related to laws, but more to how laws are created by culture.

That said, it is not insignificant that the film opens with the gathering of a family and generations, in a way that wouldn’t have happened 10 years ago. That image is very modern. I just went to a wedding at Laguna Beach this summer, and there’s 200 family members gathered and 35 cousins, and this is the result of the end of Proposition 8.

Anyway, I’m more hopeful in my own life, and I think the film reflects that.

Script: Is there any particular scene that’s a favorite of yours?

Sachs: I met this older, maybe 60-year-old gay man in Chicago, and it was really touching to me that the scene that affected him most was Alfred Molina at the party of the two gay cops. [In the scene, the living room is filled with drinking, dancing youth, as temporary occupant, George, sits unnoticed.] He said, “It’s my life. I always feel out of place, trying to fit into a world in which age is such an obstacle.” And I was touched by that. I had just thought of that scene as being about discomfort because it’s not your home, but it was a really personal response from him. I love that the film has access points for people. Another woman came up to me and said, “My grandson is just like that kid.”

Actually, what we set out to do was to write a multi-generational family epic set in a cramped New York apartment. It’s our Magnificent Ambersons!

Script: I’ll tell you my favorite scene, which has been haunting me: the one in which Marisa Tomei, as the working mother and novelist, is trying to write while her husband’s uncle, who has moved in for an indefinite time, is chattering away, oblivious, and distracting her. I swear, I could read in her eyes not just frustration, but the realization that, “Oh my God, is this the way it’s going to be for the next five years?” I think it’s some of the best acting she’s ever done.

Sachs: I’ll tell her tonight! You know, Marisa Tomei can write paragraphs for me, as a filmmaker, without a single word of dialogue. There’s a whole conversation going on. You’re reading internal thought. That’s a beautiful thing in an actor.

I think it’s wonderful, you said it haunted you. I knew it was a funny scene, but I didn’t know I’d have brilliant comic actors. Their background in comedy is as significant as their background in drama, and their timing is beautiful to watch. Just watching the craft in that scene is wonderful.

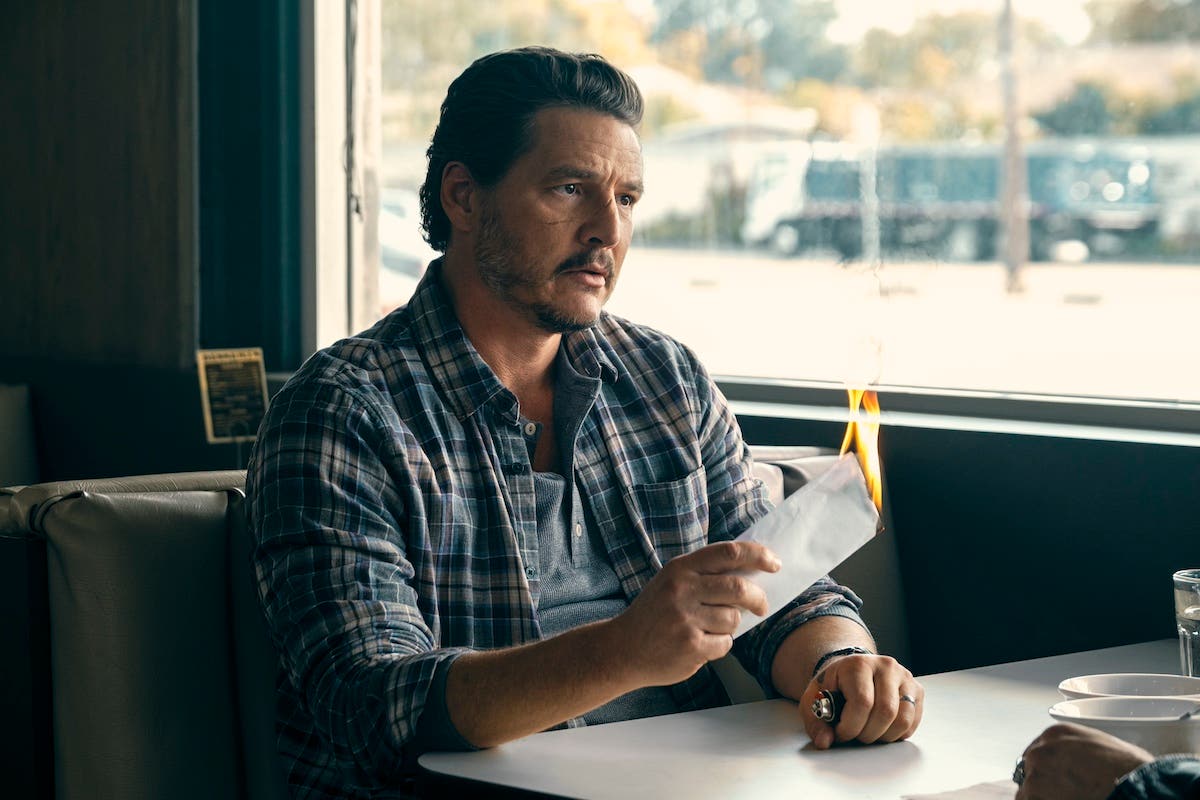

Click on the image to read Scene 22 of Love is Strange:

Bob Verini is the Los Angeles-based theater critic for Daily Variety, for whom he also contributes features on film, theater and television. Since 2000 he has been a senior writer for Script Magazine, also their resident go-to guy for all things Oscar related, and a frequent moderator of live screening talkback sessions and podcast Q&As on industry topics. By day, Bob is an academic director and teacher for Kaplan Test Prep and Admissions, welcoming your questions on standardized tests and stress management issues. Twitter: @BobVerini