FROM SCRIPT TO SCREEN: Paul Haggis On ‘The Next Three Days’

Oscar-winning screenwriter Paul Haggis discusses the importance of finding the central question in your story, creating original plot points, his writing process and more.

Originally published in Script magazine Nov Dec 2010

David S. Cohen is a freelance writer, photographer and documentary filmmaker. His articles on film and television have been seen in print outlets around the world, including US Weekly, Premiere and Variety special reports.

The Next Three Days is a departure for Paul Haggis. The Oscars® for Crash left him well-ensconced as a writer of intelligent dramas, and the success of Casino Royale, on which he shared credit, showed he could bring gravitas to a tentpole franchise. With his newest picture, though, Haggis remakes a French movie about a schoolteacher who must break his wife, who was wrongly convicted of a crime, out of prison.

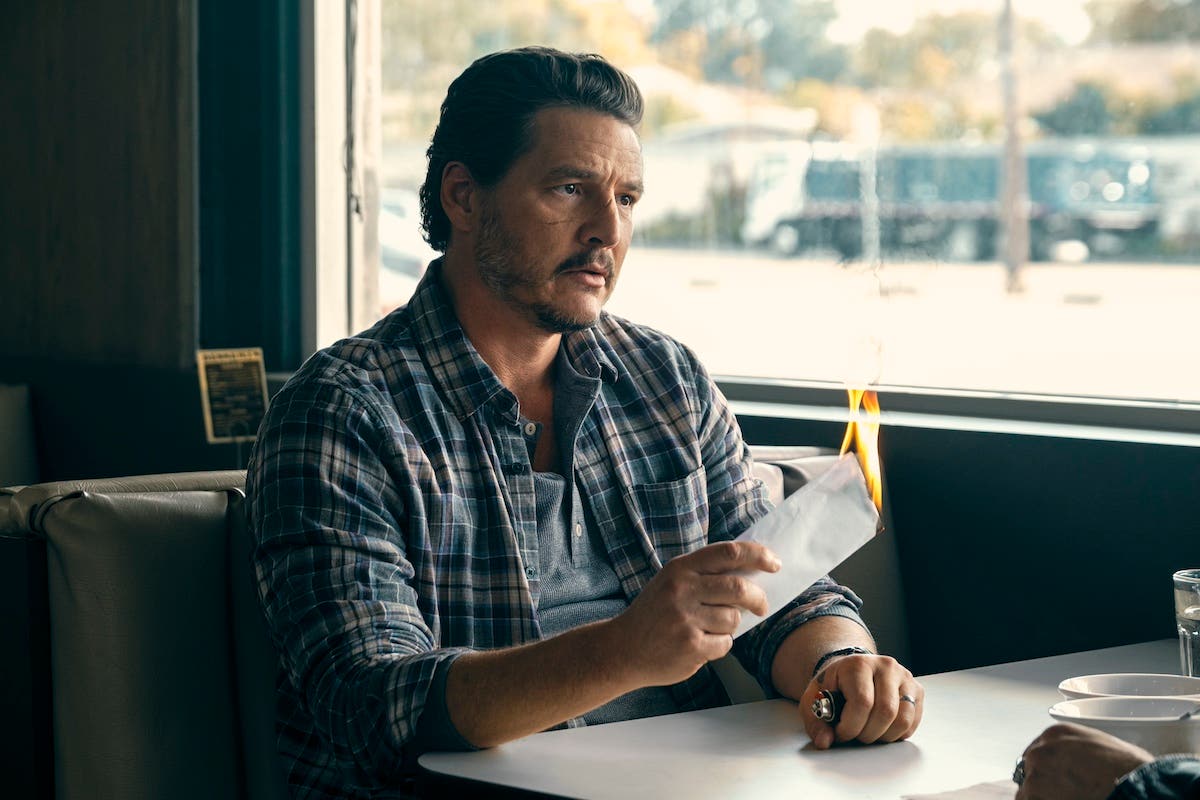

Russell Crowe plays John Brennan, a community college English teacher with a beautiful wife, Lara (Elizabeth Banks), and a young son. But Lara is accused and convicted of the murder of her boss. Three years later, with overwhelming evidence against Lara and all appeals exhausted, he begins to explore the idea of breaking her out of prison. The planning becomes an obsession that puts him in personal danger and leads him to acts of desperation and violence that would once have been unthinkable for him— and are usually unthinkable for a movie hero.

SCRIPT: Tell me about the French movie and how you found it.

PAUL HAGGIS: Well, I was trying to do a film about Martin Luther King Jr. Another really wonderful writer had written it and we just couldn’t make the budget work. So, I started looking for something I could direct because I was starting to feel a little antsy. My head of development, Eugenie Grandval, showed me this new French film called Pour Elle. We were eyeing it for our company and trying to find someone to write and direct it. I’d always wanted to do a little thriller. I’d always loved films like Three Days of the Condor, those romantic thrillers. So, I said, “Why not me?”

I think they were kind of surprised that I’d want to do a thriller. But, it’s a lovely, slight, 90-minute film, the French film; it’s basically very plot-driven. They made it quite clear from the beginning of the film, she was innocent, and that he was loving, and he’d do anything to get her out, and, in the end, they lived pretty much happily ever after. The bumps along the way were good but I thought I could make him pay a larger price. So, the first thing I did was ask myself what the question was. I need to have a question if I’m starting a movie. The question I came up with, and I’m not sure if it’s reflected in the film or not, but it’s what I was writing toward, was: Would you save the woman you loved if you knew that by doing so you’d become someone she’d no longer love? That interested me. And that wasn’t in the French film at all.

The whole issue of innocence was fascinating to me because I didn’t necessarily want to say whether she was guilty or innocent. I just wanted John to be the only one who believes she’s innocent. The evidence is overwhelming. Even his parents think she’s probably guilty. Even their own lawyer. Yet he still believed ... and what that level of belief does for someone, how infectious it is. So, those are two things I was playing with.

I start the film differently. I start with a catfight. In the French film, they’re coming home from dinner—they’re loving, they’re kissing, you’re starting to think, “Oh, this woman’s innocent.” You just know from the beginning. I wanted a scene in which you see that she has a temper by creating the Erit character who’d get under any woman’s skin. So, you later think back and say, “Oh, she almost clocked that girl. She could have gotten into a fight. She could have done something. She could have hit her boss.” So you have doubt. I did things like that.

SCRIPT:How does John differ from the character in the French film, and how did you see him?

PH: I just sat down and said, “If I had to break the woman I love out of prison, how would I do it?” I’d go on the Internet, that’s the first thing I do. I’d Google “How to break out of prison.” So, that’s exactly what I did. I went on and Googled “How to break out of prison,” “How to break into a car,” and found these fascinating things, and I just used them. I figured that’s what he would do.

I also knew I would fail spectacularly, at least at first. But then I would continue. And I’d get the shit beat out of me, and I would trust the wrong people, and I would do the wrong things. I’d start to feel really good about myself, that I’d figured the whole thing out, and then something would go wrong. I would just keep going until I either was caught or we got out or something happened. That’s what he does. So, I just tried to make him an everyman.

I loved the fact that this guy was also an English teacher, so he was a romantic. He was talking about Don Quixote. He’s got this whole romanticized vision of how you sacrifice yourself for a woman, how you go about something like this. It’s terribly romanticized and so completely impractical.

And there were other things. For example, I’d see the French film, and there’s a scene in a bar that’s exactly like one in my film. He goes into the bar (asking for someone who can forge passports) and gets the shit beat out of him, and then somebody overhears the dialogue of that conversation and follows him home and says I can solve your problem. I was asking, “Well, how? How does he overhear them? There’s loud music on. You’re in a bar. How the hell do you overhear him?” Okay, I’ll make the character deaf and he reads lips. I kept doing those kinds of things, so it wasn’t so convenient.

SCRIPT:This is really a prison-break movie, but you’re playing with the conventions of the prison-break movie, which are that the prisoner is innocent, and he or she is doing the right thing.

PH: Exactly. I had a conversation with Robert McKee. I took Robert’s class twice in the 1980s. When I went to New York, I gave him a call and said do you want to have breakfast? He said sure. He didn’t remember I’d taken his class. We had a lovely time. I just was writing The Next Three Days at that time. I said I’m doing this little thriller and I described the plot to him. He said, “That’s not a thriller. That’s a caper movie.” I said, “I’d always assumed caper movies were the Cary Grant type of movie where everything’s kind of light.” He said, “No, no, any prison-break movie is a caper movie. You set the stakes and you do your planning, and Act Three is the escape.” So, I guess what I’ve written is a caper film.

SCRIPT:Is that a bad thing?

PH: No, I like it. I think it’s kinda cool. It was interesting because you have to keep the stakes. It’s a long, slow burn to a chase scene, with a lot of bumps along the way. When we were testing, movie people said, “It needs pace, it needs pace.” No, it doesn’t really, it’s purposely slow. But you have to have the emotional stakes there, that’s what drives it in the first act, and in the second act there has to be the planning goes wrong. It goes wrong, and he goes back, re-does his plan, gets it right. Then [his plan] goes wrong emotionally. When things happen, he has to make decisions, and they’re really hard decisions. I love movies where characters have to make really, really tough moral choices.

SCRIPT:Prison-break movies don’t thrive on moral ambiguity. This movie is full of moral ambiguity, which is part of why it’s unsettling.

PH: Yes. That was not in the original, and that’s what I wanted to add. Also, things like the whole idea of leaving his son behind. In the French film, he just went to get him and that was it. But I wanted to say this guy was turning into a man who would actually leave his son behind. In order to reunite his family, he’s going to destroy his family.

SCRIPT:But you also set that up with the conversation with Liam Neeson’s character, Damon Pennington, who specifically challenges him by saying don’t start this unless you are someone who can leave his son at a gas station.

PH: Yes. That’s where I got the hint. There is a character in the French film who does give him that speech, and that’s where I got the idea. I thought, “Ooo-ooh. Hold on. We have to really test this character. What does he love the most? He loves his son and he loves his wife. Have him make a choice.” It’s easy to sacrifice yourself. Any hero will do that. But sacrifice your son? That’s harder.

Or turn into someone who’s not heroic, who would do that? His wife looks at him completely differently. In the French film, they escape, they’re happy, it’s fine. In my film, when they escape, there’s no big kissing scene—she walks by him very tenderly and looks at him and tries to smile, and then they’re in separate beds.

The audience sees the ending and they see him taking a photograph and they think, “Aw, isn’t that sweet? It reflects the photograph from the beginning.” But the photograph at the beginning had three people. In this one, there are two people. So he got what he wanted, he reunited his wife and his son, but at what cost?

It’s a question in the end, it’s not a statement. The question is, “Will they reunite? Will they be a family again?” Not “They will never be a family again” or “They will be.” A question, that’s what I want. I like those questions. What happens when the escape is over? That’s why I called it The Next Three Days. Because you’ll notice all the cards are “The Last Three Months,” “The Last Three Years,” ...

SCRIPT:... and I didn’t ever see a card that said “The Next Three Days.”

PH: There isn’t one. I was interested in what happens at the end of the movie, what happens in the next three days. So I wrote the whole movie to lead up to what I’m really, truly interested in (laughs).

SCRIPT: And then we don’t get to see it.

PH: That’s correct.

SCRIPT:Let’s talk a little bit about transitions. You don’t indicate the passage of time and you’re trusting the audience to keep up, but we hear so often about studio notes saying they’re worried the audience won’t get it.

PH: Lionsgate was very supportive, they basically let me do what I wanted. Studios do want things to be fairly clear, but in this case they knew we were trying to do a smart thriller, a thinking-man’s thriller, and so they went with it. I think audiences love figuring things out for themselves. I think you really have to respect your audience. That’s my kind of filmmaking.

SCRIPT:At the end, there’s a flashback that shows someone else committing the murder.

PH: It’s interesting. If you actually look at what I’ve done, I’ve shown you the cop sitting there reconstructing in his mind what could have happened. Not what did happen. But film is such a powerful medium, when we see something like a flashback, even though we have a point of view on it, we assume it to be true. It’s very difficult once you show something to then continue to remind people it’s not necessarily true.

By that point we want her to be innocent so much we’ll believe anything. So it’s really hard to tell a dark tale. And that’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to take a little French film and make it darker, because I thought that was particularly perverse of an American filmmaker.

SCRIPT:She gets that kiss from her son. She gets her happy ending.

PH: But, does he? What price did he pay? I bet you won’t find a soul coming out of the theater that thinks what I think. They all want a happy ending so desperately, they’ll create it themselves even if the filmmaker didn’t.

SCRIPT: Somebody compared this film to The Fugitive. But The Fugitive has the set-up of a classic prison-break movie: You know he’s innocent, and he’s trying to do the right thing. You really push this idea in the other direction.

PH: I think it’s probably less satisfying of a film because of that, ultimately.

SCRIPT:It’s not comfort food.

PH: Yeah. That’s what I wanted. I like playing with genres. I’ve always done that. I love taking a genre and just twisting it a bit. It’s what I did in Casino Royale. Really honoring it, but just twisting it.

SCRIPT: There’s a moment where she says she did it. You’re saying she might be telling the truth.

PH: That’s correct.

SCRIPT:Well, do you know whether she did it?

PH: No. I’m not her.

SCRIPT: Is it important to the story whether she did it?

PH: Not at all. It’s all about his belief that she’s innocent. He has to believe she’s innocent. That’s all I care about. That’s why you never saw a flashback from her perspective. It matters to me that he believes her. So that’s why I don’t know.

He has to believe in her, he has no other choice. At the one point where she says she did it, he’s shattered for 30 seconds, then he comes back and says, “I know who you are, you didn’t do this.” She cries, but is that because it’s fabulous to have somebody believe in you, even if you don’t believe in yourself. Especially if you’re guilty.

SCRIPT:Let’s talk about getting this film set up. You must have a certain amount of clout. You’re in a good position for people to have confidence in you.

PH: It still had to be a small film. I believe in independent filmmaking. This was a reasonably budgeted film and Russell did it for considerably less than he usually does movies. Although it couldn’t be described as a passion piece, it was a smaller picture. For that reason, there are things you could do and couldn’t do. I like those constraints. Example, the whole ending where the cops are coming and they’re going to search the plane. You never see a plane. Why? Because it’s going to cost me $150,000 to get that plane. What I can afford is three seats. So, they search the gangway. I like those kinds of problems. It makes me more inventive as a writer and a director.

SCRIPT:Where else did constraints make you think creatively?

PH: Early on, when I was writing the script, I decided I needed to shoot it in a place that has a tax incentive, so I decided to research cities where there were interesting prisons or jails that had a tax incentive. I settled on Pittsburgh. The jail there happened to be the largest jail in the world, a brand-new jail. I saw that and thought, “Wow, this is so different. It’s so modern, it’s so inhuman.”

I went to Pittsburgh and figured out what the breakout was. I wrote it exactly for all the locations. It’s so disheartening when you write something that you see, and it’s just wonderful, and the director comes and says, “We don’t have those locations. You can’t shoot there.” It was one of the many things that went wrong with Quantum of Solace. I wrote it and the director said, “No, we don’t have that. We don’t want a winter scene, we want a desert scene.” Oh. Oooo-kay. It’s so much better if you write it for locations you already know you’ve got. I’m really inspired by the physical environment as a writer and a director.

SCRIPT:Can you tell us about where and how you write?

PH: I usually write in public. This one I wrote mostly in New York, in three or four coffee shops and the lobby of the Mercer Hotel. I like to write in public because you’re so isolated as a writer, and you want to know that life is going on, even if you’re not a part of it. So you sit in the corner and find a table where no one will disturb you but you hear all those voices, and it fools you into thinking you’re part of life.

I go through phases. On Million Dollar Baby, I sat and wrote in my study for a year. On Crash, I wrote the story by myself and then wrote the script with Bobby [Moresco] in my study. After that, I’ve been feeling the need to feel like I’m more a part of life. I do a lot of the rewriting in my loft or my office. But writing originals, I get antsy. I can write for three, four, five hours in my loft, but after that, I’ve got to get out.

SCRIPT:What would you like writers to know about your process of writing this film and getting it made?

So, that’s exactly what I did. Oh gosh, writing is always really uncomfortable to me. I love classic genres, I love trying to subvert them wherever I can. I think there’s a great risk in doing that at times because it can make the film a little less satisfactory an experience for the audience, but I think in some cases, it satisfied me more. I like taking risks and hope I’ve done it again here. I think that’s what writers love to do, we love to take risks.

- More articles by David S. Cohen

- From Script to Screen: 'Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind'

- Alt-Script: What the Heck Does Independent Filmmaking Mean?

Get tips on the specifics of writing crime stories in Jon James Miller's webinar

Devil in the Details: Writing the True Crime Documentaries and Podcasts