Good Vibrations: Screenwriters Stephen and Jonah Lisa Dyer on Hysteria

The vibrator was invented by a man: a doctor, in fact—an upright, uptight doctor in Victorian England. That’s an amusing notion, isn’t it? It also happens to be true. But…

The vibrator was invented by a man: a doctor, in fact—an upright, uptight doctor in Victorian England. That’s an amusing notion, isn’t it? It also happens to be true. But can you make a movie out of it?

That was the challenge presented to the husband and wife screenwriting team of Stephen and Jonah Lisa Dyer by producer Tracy Becker (who first heard the story from writer Howard Gensler) and director Tanya Wexler —to develop a one line pitch (“Victorian doctor invents vibrator”) that at first glance might have seemed suitable only for a quick gag or sketch into a feature length narrative. The Dyers accepted the challenge and succeeded admirably, transforming a potentially one-joke idea into a charming, hilarious, multi-faceted screenplay that is part farce, part romantic comedy, part social satire, part spoof (one that makes wonderful hay of the all of the tropes and conventions of Merchant Ivory/Masterpiece Theater-type period pieces), and part history lesson (illustrating that London in the late 19th Century was a nexus of progress in medicine, science, and women’s rights).

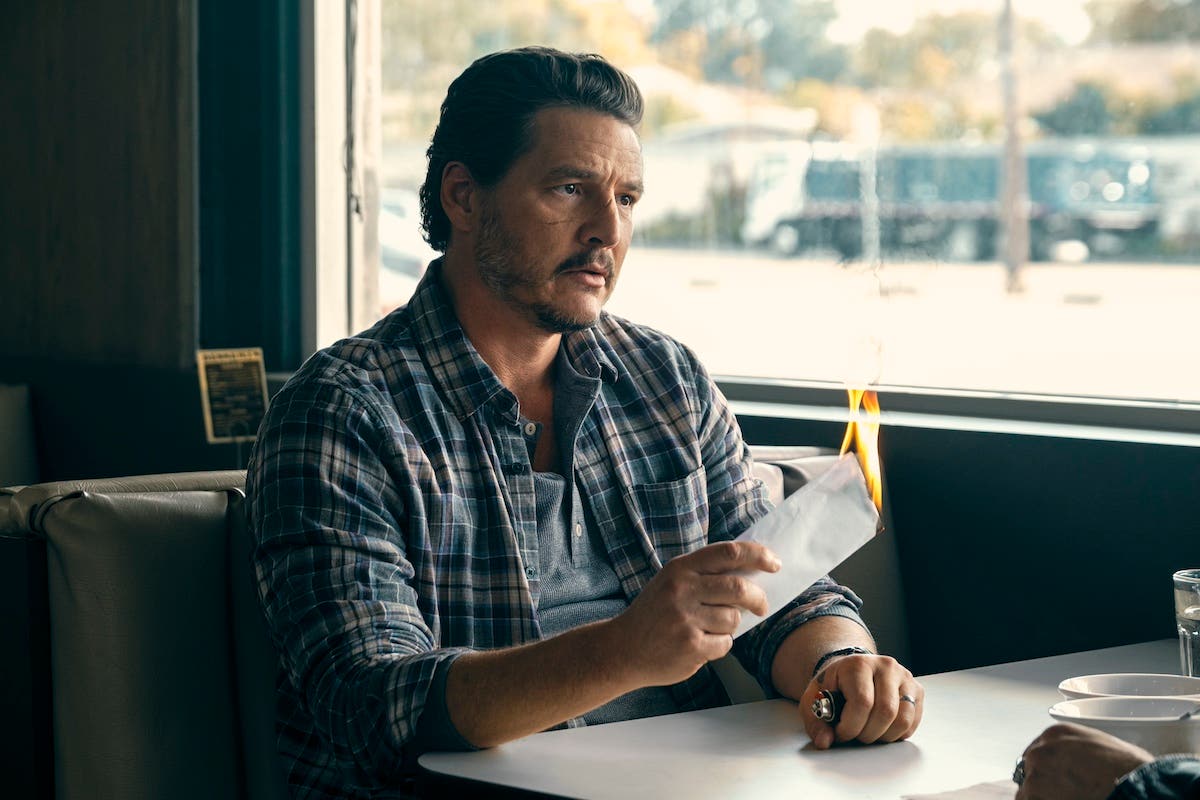

Hysteria tells the story of Dr. Mortimer Granville (Hugh Dancy), an earnest young doctor in 1880 London. Unable to find or keep a job because his progressive ideas about sanitation and germ theory offend the medical establishment (which, at this time was still putting its faith in leeches and hacksaws), Granville finally accepts a position assisting Dr. Robert Dalrymple (Jonathan Pryce), the city’s leading gynecologist. Dalrymple specializes in treating “hysteria” —a catchall phrase that male physicians in that repressive, patriarchal era used to describe just about any “female” problem that they couldn’t understand, from weeping to melancholia and anxiety, hyposexuality and hypersexuality, marital dissatisfaction and simple boredom. Dalrymple’s treatment – manual “medicinal massage” of the female organs “to the point of paroxysm” – proves to be so popular with the ladies of London that before long the good doctor is in desperate need of “another pair of hands.” Soon after joining Dalrymple’s practice, Granville finds himself engaged to his employer’s daughter Emily (Felicity Jones), the epitome of proper Victorian maidenhood, but also vexed and intrigued by Emily’s sister, Charlotte (Maggie Gyllenhall), a feisty social worker who challenges Granville to put his medical talents to use helping London’s less fortunate. Proving to be even more adept at medicinal massage than Dalrymple himself, Granville becomes so busy that he begins developing painful hand cramps. Adapting a motorized feather duster invented by his friend Edmund St. John-Smythe (Rupert Everett), a wealthy eccentric who is fascinated by electric-powered technology (then in its infancy), Granville develops an electric massager that he initially uses to relieve his cramps. Before long, however, it’s being used for far more intimate purposes, with surprising results for everyone involved.

The Dyers recently spoke to Script about their work this very unique, very funny film:

SCRIPT: How did you two begin writing together?

JONAH LISA DYER: Well, for years I was an actress and Steven was an independent film producer—he produced a film with his sisters called Late Bloomers that was at Sundance in ‘96—and I acted in that. And we had started dating before we made the film, with no idea of being writing partners one day, and we went on that track for a while: Steven as an independent producer and me as an actor. We moved to New York; he worked with Tanya Wexler on two films together [Ball in the House, Finding North]; and I started doing stand-up comedy. We worked together writing my stand-up material and realized that we were really good writing partners. We enjoyed it and we were really funny together.

STEPHEN DYER: Sometimes we were funny…

JONAH LISA DYER: (laughs) Yeah, sometimes. And it just kind of blossomed out of that. There was an idea that Steven had been trying to pass on to his sister Gretchen, who is also a screenwriter—she wrote Late Bloomers—and she just didn’t really spark to it and I finally said “Stop trying to give that idea away, it’s a great idea. We should write it.” And we gave it a shot and we ended up with something that was not horrible. And a longtime friend and agent, Lawrence Mattis, really liked and we went out with it and got some attention and kind of all of a sudden were accidental screenwriters. And [then we] started developing other projects and ideas together and writing together.

SCRIPT: How did you become involved in this particular project?

STEPHEN DYER: Well, by the time we got a hold of this project, we were definitely trying to be screenwriters: we had written a couple of other scripts; we’d had something get optioned; and I was still partners with Tanya Wexler, but we were definitely not really fully in the game. And she met the producer, Tracy Becker, in New York, who kind of gave her the one-line idea—“doctor in Victorian England invents the vibrator” —and Tanya was ‘Okay, I have to direct that movie.” So Tanya somehow convinced Tracy Becker to let us have a go at it. And [then] we started working seriously—trying to figure out what we had. We literally just had no idea at all.

JONAH LISA DYER: No idea how we were going to do it; what our take was; nothing.

STEPHEN DYER: Nothing.

SCRIPT: One of the terrific surprises of the movie was what you did with it, because one could imagine kind of a one-joke movie, but you took it in so many interesting directions. Can you talk about how you developed the story that you did?

JONAH LISA DYER: I was working for [screenwriter] Bill Broyles when they gave us the idea, and I ran it by him at one point and he was like, “Wow, the trick is going to be making it not just a Saturday Night Live skit.” We instinctively knew that too: “Yeah, that’s a really good gag, [but] it’s got to have a story. It’s got to be about something.”

STEPHEN DYER: It was so naturally funny—that’s why we said yes to it. I mean, you tell people the idea, they immediately either smile or laugh. They just can’t help themselves. And so, knowing that we had that in our pocket, it really was, “Okay, but there has to be characters and a story and what’s the story about?” We looked at a lot of different movies and I think that some of the movies that structurally made sense to us were romantic comedies, but also screwball comedies that seemed to have thematics underneath them. And I think we began to zero in on that idea of progress, which was ultimately the cornerstone of what the movie is really about: how does progress happen and how does progress get stymied by the status quo? Medically, [Granville’s] stymied by the status quo, and electricity is stymied by the status quo. And I think for Maggie’s character—she can see into the future probably further than anybody, but is very stymied by, again, the status quo. So, the movie is about progress getting stymied by the status quo, and the people who are convinced to try to change that, and the efforts that they go to and the struggle that they have to enact change.

JONAH LISA DYER: So much of it came out of the research: the books we had on Victorian medicine, on women in Victorian England, and the suffrage movement, and electricity. All of that stuff was all circling around at the same time [the 1880s], and so we realized fairly quickly into the research that this was a really ripe time for innovation across the board, and how interesting that is, and what a fabulously rich period of time that is when you have the old and the new really bumping up against each other like that.

STEPHEN DYER: I think for us there were three fields: medicine, electricity, and women’s rights, and we tried to find a unifying struggle—each of those people were struggling for progress in their own way—that would bundle those three things together.

SCRIPT: Mortimer Granville was a real person, so how much of the story that we see in the film is real and how much of it is invented?

JONAH LISA DYER: Very little of it is real. I mean, the doctor’s name is Mortimer Granville; he is credited with inventing the vibrator; he was a pretty straight-laced guy; and kind of horrified that his invention would be used in the context that it’s now used in.

STEPHEN DYER: He didn’t invent this initially to treat women. It was sort of an electro-massager, but it very quickly found a home doing what it does in the movie.

JONAH LISA DYER: I don’t think he really was a hysteria doctor.

STEPHEN DYER: We actually found some books that he had written, but they were very dry, sort of academic stuff, and there really wasn’t a lot of information about him personally. So, we had to invent all those characters and their interrelations.

JONAH LISA DYER: We basically made him into who we needed him to be into to serve the story.

SCRIPT: Can you talk a bit about your writing process? Do you write in the same room together or do you split the work up and write things separately?

JONAH LISA DYER: It’s kind of all of the above. We have young children—our kids are six and three—so its kind of fly by the seat of your pants, and on a day-by-day basis we kind of work how we can work. Sometimes we work on things together [and sometimes its] “You do three scenes and then I’ll read them and give notes.” We kind of shake it up every time. On Hysteria, Steven pounded out the rough draft and then we started working back and forth once we had something on paper.

STEPHEN DYER: We work a lot from treatments. In fact, as time has gone on, we’ve become more and more determined to really try to hammer out as much as possible in a prose document and then one of us will [do] the first draft.

JONAH LISA DYER: Right, we’ll hammer out that treatment together, both in the room, and come away with this fifteen-page document that one of us will then go and basically plug into the format.

STEPHEN DYER: And then once we’re really editing, it’s really like a free for all. It’s a struggle to get to a final product, but for us there’s a sort of net positive, which is it has had to clear two people’s judgment and get through that process before it gets to somebody else. So I do think that that sort of struggle to agree on the final material is beneficial in the end, simply because it’s a rigorous process.

SCRIPT: How long did you work on the script?

JONAH LISA DYER: They gave us the idea in 2004.

STEPHEN DYER: We started working on it in 2005, it was made in 2010, and now we’re a year-and-a-half from that. So, a quick six to seven year process.

SCRIPT: How many drafts did you do?

STEPHEN DYER: A first draft, a big revision, a second big revision that cracked the third act plot, and then lots and lots of small stuff along the way.

SCRIPT: Did you do any rewriting during shooting?

JONAH LISA DYER: We were on set for the entire shoot—we sometimes had work to do and sometimes were just kind of voyeurs and that was really fun. But we did get to do a few specific work things on set—nothing big at all. It was mainly when an actor would say “I can’t get my mouth around this.” [Basically], the movie that was shot was the movie that we had turned in.

SCRIPT: How do you feel about the response the film has been getting?

JONAH LISA DYER: We saw it in Toronto [Hysteria was an Official Selection at the 2011 Toronto International Film Festival] and it was raucous. There were jokes that were missed because people were still laughing at the joke before, and we were like, “Oh my god, if we had known we would have put more air in the bag there.” It was amazing.

STEPHEN DYER: We’re psyched. It feels good. I think, like everybody, we’re a little bit nervous before it opens, but we’ve heard about enough screenings now that we feel pretty confident that it’s funny.

JONAH LISA DYER: I felt that way when I was seeing it being shot, when I was seeing the dailies. I was like: “Oh wow! I think this is going to be really funny. I think we got it!”

Hysteria opens May 18, 2012.

Ray Morton is a writer and script consultant. His many books, including A Quick Guide to Screenwriting, are available online and in bookstores. Morton analyzes screenplays for production companies, producers, and individual writers. He can be reached at ray@raymorton.com. Twitter: RayMorton1