BEHIND THE LINES WITH DR: Writing Process and Laying Bricks

Doug Richardson explains how the writing process is akin to laying bricks… and fixing work gone wrong.

Doug Richardson's first produced feature was the sequel to Die Hard, Die Harder.Visit Doug's site for more Hollywood war stories and information on his popular novels. Follow Doug on Twitter @byDougRich.

There’s a comment I often hear. It’s usually in response to a story I’ve told, relating some sort of showbiz battle I’ve won, lost, or merely survived.

“What you do sounds sooooo hard.”

Now, I do understand the context. And it’s usually something having to do with the intense nature of the business I’ve chosen. Or how fiercely competitive screenwriting is, let alone how damned difficult to succeed at.

Yet here’s how I normally reply. It’s not spin. It’s just me.

What I do is not hard. I know hard. Digging ditches is hard. Manual labor is hard. War is hard. Fighting disease is hard. I have a seventeen-pace commute to my office. I most often work in gym shorts and flip flops. I use my imagination and get paid for it. Like I said, what I do is not hard. It is, at worst, very difficult to excel at. But not what I would describe as hard.

Okay. So maybe rewriting is hard. Then again, now that I think about, maybe it’s really not.

Now that we’ve set the parameters, we can talk character. Mine. I’ve been described by some as tough. Stubborn. Difficult. Too opinionated. Intimidating. Moody. Hell, even some of my daughter’s friends have expressed to her that they’re scared of me. I’ll let you make your own assessment of that.

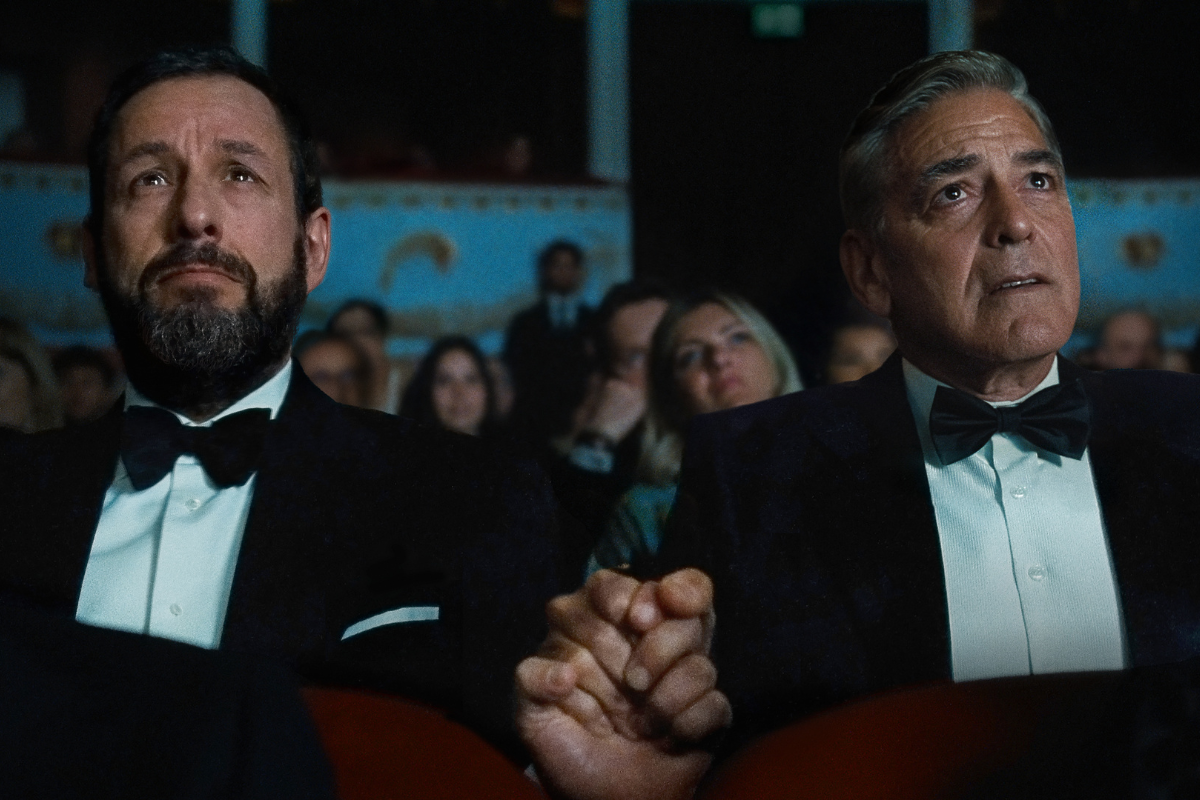

Yet these assertions of my character sometimes strike me as odd. I think of myself as a teddy bear. A hard candy-coated covered mush of warm gooey affection. Someone who cries at the slightest movie sentiment. A pushover if you ask me nicely. Then I take a look in the mirror and who do I see? My old man. A guy who still scares the shit out of me.

Yeah. That guy.

How do I describe my father in a succinct manner? How’s this? When I was having an initial meeting with a psychiatrist, he asked, “Tell me about your father.”

Really? I asked myself That old cliché?

“Hard to describe,” I finally replied. “But John Wayne comes to mind.”

“You mean he’s dead?” quipped the shrink.

I laughed out loud. “No I’m afraid. He’s still with us.”

I went on to tell this story. It was a gazillion damn years ago. I forget exactly how old I was. Ten maybe. We lived on a small ranch-slash-farm where we boarded dogs as a second income. There we raised all matter of animals and fauna. My father had an entire half-acre dedicated to his vegetable garden. My daily summer duty was to toil there from eight until a near sizzling noon. I did this alone due to my sisters having recently been permanently reprieved from outdoor chores in lieu of helping out our mom in the air-conditioned house. For company I’d replaced my annoying older sibs with a portable, AM radio. I’d park it on top of a fence post, tune in to the local Top 40 station and crank up the volume until that cheap little speaker deformed. My pop hated that radio. He was certain that listening to music made for lazy work. Yet one day, while he’d stopped by to observe the quality of my labor, he somehow lent his one good ear to the Johnny Cash hit, A Boy Named Sue.

Now, if you’ve never heard the song, here’s a link. Listen and continue.

I was quite aware that my pops was lending his nearly deaf ears to a song that could best be described as a celebration of child abuse—the father in the song purposefully handicapping his son by saddling him with a girl’s name so he might grow up tough as leather. The song ended and, just around the time I was wondering how my dad had processed the totality of Johnny Cash message, he said:

“I really like that song. I completely agree with it, too. Maybe I shoulda named you a girl’s name.”

And that was that. My pops thought I needed less tenderizer and more Kevlar in my veins.

So there it is. I’m a product of nature AND nurture. Though nurture isn’t quite the word I’d use.

Fast forward a couple of years to an afternoon where I was raking the grass I’d just cut. As my pops had feared, some song on the radio had turned my strokes into something that made me look as if I was perhaps slow-waltzing with the rake. That best friend of a radio was perched on a back stoop. I recall the door flinging open and, in slow motion, my father place-kicking that radio into fractured oblivion.

The hurt I felt was unimaginable. I’ve since tried to look at the situation from my dad’s point of view. The best I can do is think it mustn’t have been a Johnny Cash tune that was playing.

One last anecdote and I’ll make my point.

Not terribly long after my radio had been obliterated into plastic gravel, my father set out on a home beautifying project to please my mom. It involved building a series of brick planters around the house. Pallets of new brick were piled into the back of our pickup and guess who had to off-load the load? But that duty was no big deal compared to the actual mason-work required.

Along the north edge of our house my dad planned to build a planter to fit the entire length. He dug out the trench and poured the concrete base. Then with his trusty assistant—me—we laid the first neat row into a bed of wet mortar. Our tools were a masonry trowel, a carpenter’s level, and thirty feet of twine stretched between two stakes pounded into the dirt. Once he felt I had the hang of the gig, my pops moved on to some other task on the far side of the property. I was on my own. Solo without a radio.

After a couple of hours and Lord knows how many repeating Top 40 hooks in my brain, I was feeling pretty damn pleased with myself. I liked the brick work. It was uniform, peaceful, and gratefully under the shade of a two-hundred-year-old oak tree. I’d nearly finished the chore when my father reappeared. He stood at one end of the planter and asked me what I’d thought of the job I’d done.

“Pretty good, I think.” I stood up and admired my effort.

“Come look at it from here,” said my old man, inviting me down to the end where he stood. “What do you see?”

Once I was on the same line where my father stood, I could see what he saw. There was, nearly halfway down the planter, a quarter inch jog. As if the brick wall zagged just a notch before continuing down its perfectly straight line.

I instantly knew how it had happened. Somewhere, in my first masonry outing, I must have barely nudged one of the stakes, thus causing the minute alteration in trajectory.

As errors go, it wasn’t horrible. But my mother, who had the inner ear of an Apollo astronaut and could probably balance the scales of justice while on Quaaludes, would never have approved. I instantly realized that I practically would have to start the job over from scratch. If only I’d had the moment to verbalize my conclusion.

My father, using that same steel-toed boot he’d employed to murder my radio, knocked down the entirety of my hard work, turning it into a long pile of brick rubble.

I’d already learned not to cry in front of my old man. So I dammed up the tears until he’d vanished back into the house. Then once I’d finally composed myself I started over.

To me, that work was what I’d call hard. It hurt both emotionally and physically. And it wasn’t the least bit satisfying once I’d completed the job.

What the work did though was make me that much tougher. On myself as well as others. The thick skin which one must acquire in this business had already been installed before I’d first embarked on a showbiz career. Thanks, in part, to my dad and some boy named Sue.

I’ve spent months working on certain projects. Only to realize—or be made to realize—that the work I’d poured so much sweat equity into required a remodel. Or a total do-over. A teardown that demanded I start over from the beginning. When such realizations occur, I’m always reminded of that brick planter. And if I could rebuild that, I could rebuild anything.

Now, if you’ll please excuse me. I’m going to call my dad to tell him I love him.

- More articles by Doug Richardson

- Primetime: Getting Your First Job in Hollywood

- Meet the Reader: Rewriting is Writing

Get FREE Screenwriting Downloads to help with your writing process and career!

Doug Richardson cut his teeth writing movies like Die Hard, Die Harder, Bad Boys and Hostage. But scratch the surface and discover he thinks there’s a killer inside all of us. His Lucky Dey books exist between the gutter and the glitter of a morally suspect landscape he calls Luckyland—aka Los Angeles—the city of Doug’s birth and where he lives with his wife, two children, three big mutts, and the dead body he’s still semi-convinced is buried in his San Fernando Valley back yard. Follow Doug on Twitter @byDougRich.